My maternal great, great grandparents; William Thomas Quennell and Mary Bruce, were both born in Lambeth County, Surrey, England in 1836 and 1842 respectively. Both of their fathers were bricklayers in Surrey and, it is reasonable to assume, knew each other. It is quite possible that WIlliam’s father employed Benjamin Bruce in his building business in Lambeth.

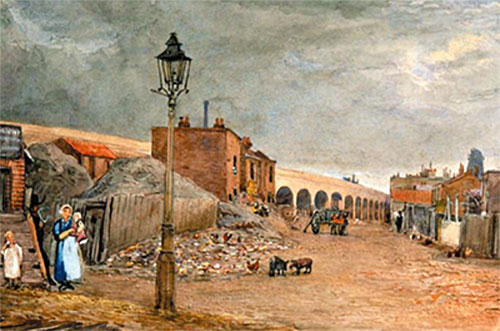

William’s boyhood home was No. 22 and later, No. 44 Lower Kennington Lane, Lambeth, Surrey – a stone’s throw from what is now ‘The Oval’ cricket ground in one direction and what was then the Bethlehem Mental Hospital (‘Bedlam’) in the opposite direction.

The Lambeth district is on the south bank of the River Thames near the Houses of Parliament and Waterloo Station and it was the centre of an outbreak of cholera in 1848-49 which killed 2000 people. The Lambeth District Sanitary Reports of 1848 describe conditions in the area including:

“…dead dogs and cats and filth of every description and although it was a cold morning, such was the offensive effluvia emitted as to render a speedy retreat most desirable …the stench was so great we could scarcely remain near the spot”. “At Lower Kennington Lane there was another large common sewer and most of the houses in this district had cesspools in the yards and gardens. The houses at Bennett’s Buildings, Kennington Lane were small tenements “wretchedly inhabited”, lying low and with bad drainage, their privies and cesspools overflowing; there was fever prevalent in the area. The report concluded: “It would appear that all parties would gladly avail themselves of the advantage of the Common sewers but that the expense of doing so deters them, and the unwillingness of tenants to lay out money upon the landlord’s property”. (The Lambeth Cholera Outbreak Of 1848-1849: Amanda J. Thomas, 2010)

Perhaps it was these deadly conditions and the opportunities beckoning for a builder /bricklayer arising from the meteoric growth of post gold rush Melbourne which motivated William T. Quennell to migrate to the other side of the world. The colony in Hobart Town was suffering a severe labour shortage because of the end of convict transportation in 1853 and also because thousands had rushed off to make their fortunes in the gold fields around Port Phillip and Bathurst. Van Diemen’s Land tried to counteract this shortage by implementing a ‘Bounty’ immigration scheme.

The system allowed for all but £5 of the immigrant’s fare (£22) to be paid for them while the immigrants were committed to work for 4 years for the landowner who had sponsored them. The indentured immigrant paid back a quarter of the money each year of their employment so that after their 4 years toil they were free of any obligation. During 1855, 5,000 ‘bounty’ immigrants arrived in Tasmania.

William Quennell successfully applied for ‘bounty’ immigration (sponsored by P.T.Smith) and on 3rd November 1854, aged 20, he sailed alone from London on the barque ‘Wanderer’. He arrived in Hobart on 13 February 1855 after a 95 day voyage. William is recorded in the ‘Wanderer’s’ passenger list (under the mispelled ‘Quinnell’) as: 20, Church of England, can read & write, native place – Surrey, general labourer, name of person on whose application sent out: P.T.Smith)

It is not known to me if William commenced his indentured employment in Van Diemens Land or when or how he made his way from Van Diemen’s Land to Melbourne. It is apparent from debate in the Hobart Daily Courier newspaper at the time that a large number of bounty immigrants never took up their contracted employment and bolted immediately for the supposed riches of the Port Phillip colony.

Mary Bruce, aged 12, sailed from Southampton with her parents Benjamin and Elizabeth and younger sister Elizabeth aboard the ‘Omega’ arriving in Port Phillip in May 1855, just 3 months after William Quennell had landed on these shores. Their intended address was recorded as ‘Collingwood’ in the Omega’s passenger list. No further details are known to me about how William and Mary developed their relationship over the next 4 years, but they were married on 9 October 1859 at St. Marks in George St, Collingwood. Mary became a bride at 17 years and 2 days old.

Their first child, Jessie Louise was born in Collingwood on 7 September, 1860. By 1860 William had been the Secretary of the Victoria Operative Bricklayers Society (No.1 Lodge) for 4 years.

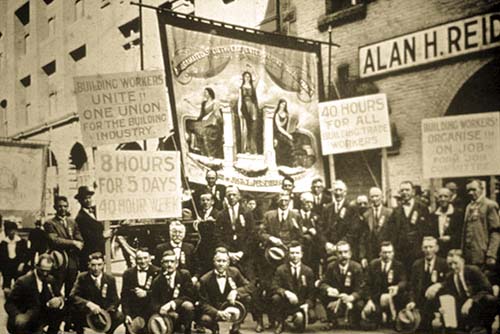

The Victorian Operative Bricklayers’ Society had been established a few years earlier (8 April 1856) at the Belvidere Hotel, Brunswick St, Collingwood …

‘for the purpose of mutual support of the Members in case of accident, and for the Burial of Members and Members’ Wives’.

Apart from the central Melbourne (No. 1) Lodge, lodges were also formed at Bendigo, Prahran and Richmond. It was an early party to eight-hour day agreements. Unlike their counterparts in the industry, Bricklayers never saw the need to become a legally registered union at either state or federal level until 1969, when it was registered with the Victorian Industrial Relations Commission.

In the mid 1850’s meetings of bricklayers were held at the Belvidere Hotel in Brunswick St. Collingwood, with the ‘8 hours question’ high on the agenda. These campaigners became known as ‘Belviderites’ , named after the hotel in which they met. The ‘Belvidere’ was later renamed the ‘Eastern Hill Hotel’ and is now a part of the St. Vincent’s Hospital complex. At a meeting on 1 April 1856 one Belviderite stated that;

“…that eight hours hard work in such a sun as that of Australia was far more trying than ten hours in Ireland” and; “Let them look at their homes and then let them ask if anything was wanted there: were there no social considerations to be taken into account ? The capitalist was not there: his influence did not extend to the moral and social advance of their families. Let them then be determined to carry out the movement and back it with all their energies and all their might”.

The following week, a set of resolutions was passed by the brickies which included:

“That this meeting, being fully sensible of the importance of a reduction in the hours of labor, resolve to initiate a society of operative bricklayers to facilitate the desired object”, to “cement a mutual brotherhood for each other’s benefit”.

Was any pun intended? The meeting also resolved to join with the Mason’s society in their efforts to achieve an 8 hour day. Thus the Victorian Operative Bricklayers Society was formed and William Thomas Quennell was elected as the Secretary of the “No.1 Lodge”.

The Melbourne Trades Hall Council grew from the historic winning of the eight-hour day by the Melbourne building trades in 1856. In that year the Melbourne Trades Hall Committee was formed to receive a grant of land on which the world’s first Trades Hall, or “Workers’ Parliament”, was built in Lygon St, Fitzroy in 1859.

In 1860 William was still secretary of the Operative Bricklayers Society representing the interests of Melbourne brickies:

To BRICKLAYERS and Others. I hereby give notice, that 15s. per day is the current rate of BRICKLAYERS’ WAGES. WILLIAM QUENNELL, Secretary, No. 1 Lodge. (The Argus: January 19, 1860)

William and Mary produced 13 children, who, in order of age, were: Jessie, Julia, Edith, William, Alice, Rosa, Frank, Henry, George, Albert, Olive (my great grandmother), Millicent and Alfred. Their first three children were born in Victoria, but the next two, William (Jnr) and Alice were both born back in Lambeth county, England. Obviously William and Mary returned to England for about 4 years from 1865 to 1869. Why did William and Mary and their 3 young children return to England? In June 1865 William Quennell had been the plaintiff in a Supreme Court of Victoria action against John Addicott, a carpenter from Collingwood. Apparently Addicott had invested in 6 brick houses in Moor St. Collingwood and it is probable that these were either built by William Quennell or he had provided Addicott with a loan. Addicott owed £600 which he could not repay, his estate was declared insolvent and compulsorily sequestered by the gloriously named and titled Chief Commissioner of Insolvent Estates, Mr. Wriothesley Baptist Noel. Presumably William Quennell was eventually paid what he was owed from the Addicott estate and this ‘windfall’ may have prompted a trip back to the mother country to see family.

At the end of his return to England, on 7th April 1869, William dissolved his Surrey building business partnership with his brother Henry. Two weeks later, on the 21st April, William, Mary and their 5 children: Jessie (9yrs), Julia (7), Edith (5), William jnr (2) and Alice (1) once more embarked at Gravesend aboard the ‘Norfolk’, bound for Port Phillip in Victoria, Australia.

Their sixth child, Rosa Victoria, was born in Richmond, Victoria. Is it possible that this daughter’s name directly reflects William and Mary’s second optimistic view of the new colony down under?

Their seventh child, Frank Line Quennell was also born in Richmond, in 1873. The unusual middle name ‘Line’ is in respect to William’s mother, whose maiden name was Julia Line. In 1874, William, still the fervent ‘trades hall’ man, attended a meeting of 400 building tradesmen at the Trades Hall in his old suburban territory of Fitzroy. The meeting was called to support the ‘Saturday Half Holiday’ movement. It was reported in ‘The Argus’ that the Chairman, Mr James Stephens….

“trusted that resolutions would be discussed in a temperate and reasonable spirit. Mr. William Taylor (mason) stated that the Saturday half holiday had prevailed at home for many years and he himself so far back as 1851 had enjoyed its benefits. In this country the half holiday would be far more appreciated and was certainly far more needed than in the more temperate climate of England. He moved “That the Saturday half holiday would be conducive to the wellbeing of all connected with the building trades and the public in general. The motion was seconded by Mr. Andrew Geddes (mason) and carried by a large majority. Mr. Mavor (plumber) moved the second resolution as follows: – “That in order to obtain the desired boon, all do agree that are in the receipt of 11s. per day and upwards to reduce the wages one half penny per hour and those in receipt of 10s. and under, to demand one penny per hour advance. The motion was seconded by Mr. James Stephens. Mr. Alfred Parrot (mason) thought that the wages question should not be touched at present and he moved as an amendment “That the resolution just read be withdrawn”. The amendment was seconded by Mr. W. Quennel (bricklayer) and supported by Mr. Elliot (painter) who thought that the question of reducing or increasing the wages should be referred to the Amalgamated Union as the proper body to deal with such subjects. After a good deal of discussion in which a person named William Evans created a deal of confusion by appearing on the platform in a half intoxicated state and telling those present that “it was all humbug and he despised them all because they were miserable wretches”, the amendment was carried by a very large majority. It was also resolved on the motion of Mr. Mavor, seconded by Mr. A. Geddes “That on and after Saturday the 25th July, all persons connected with the building trades do leave off work at 12 o’clock in summer and 1 o’clock in winter”. (The Argus: July 16, 1874)

I wonder what the crabby William Evans’ beef was? Two days later, a letter from William was published in ‘The Argus’ headed: THE SATURDAY HALF HOLIDAY: TO THE EDITOR OF THE ARGUS.

Sir, With reference to a resolution inserted in your report of the meeting at the Trades hall, that the trades shall cease work at 12 o’clock noon in the summer months and 1 o’clock p.m. in the winter months, I desire to state that the resolution in question was not passed but, on the contrary, was lost by a majority. I unhesitatingly state no such resolution was passed. Yours, &c, WILLIAM QUENNELL.

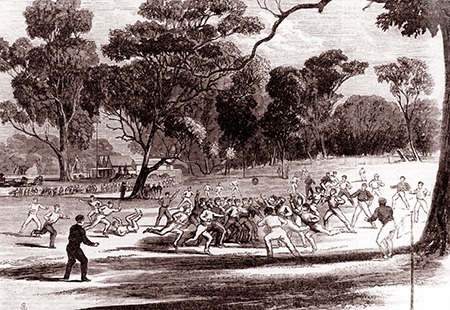

Along with the 48 hour week, it had been negotiated that by working longer than 8 hours on a ‘weekday’ a half day holiday could be made available on a Saturday. Melbourne was one of the first cities in the world where many employees had Saturday afternoons off. Australian football had blossomed in the 1860’s and provided a natural activity for such a half-holiday. Formed in 1859, Melbourne and Geelong are among the world’s oldest football clubs. They were soon followed by Carlton (1864) and North Melbourne (1869). More teams were created in the 1870s; including Essendon (1871), St Kilda (1873), and Hawthorn (1873). While football had yet to organise itself into any form of league or association, it had already infected the heart and soul of working class Melbourne and provided a crack in the dyke of the Protestant work ethic! The first recorded rules of Aussie football, drafted in 1859 included Rule 11: In case of infringements, captain may claim free from where breach occurred. Except where umpires appointed, opposing captain to adjudicate. Under Rule 11 the captains were usually responsible for adjudicating on infringements and disputations. The tragic error of appointing Field Umpires did not become a regular feature of the game until 1872.

FOOTBALL MATCHES: A meeting of secretaries of football clubs was held last night at Nissen’s Hotel, Bourke street, to arrange matches for the present season. The secretaries were successful in being able to make appointments for the greater number of the Saturdays in the season. (The Argus: May 15, 1874)

Only 3 months after the Trades Hall Half Holiday meeting in 1874, during a Victorian Legislative Assembly debate about the opening of Public Libraries, Museums etc on Sundays, Parliamentarian Woods succinctly hit the nail on the head!

Mr JAMES – “The religious bodies in this colony had done a great work and it was to the active and healthy operation of their efforts that we were indebted for the mode in which Sunday was spent. The number of children attending the Sunday schools in this colony was 111,973, and the churches could accommodate 368,890 persons. Taking these facts into consideration it could not be said that the present mode of spending Sunday was a failure. It was argued that it was for the benefit of the working classes that these public institutions should be opened on Sunday, but he would like to know how many availed themselves of the Saturday half holiday to visit these institutions

Mr WOODS – “They want to see the football on that day” (Laughter)

Mr JAMES – “If the working classes were so anxious to improve their minds as was alleged surely they would avail themselves of this half holiday. He feared that if the Assembly gave its sanction to breaking down the barrier which now guarded the day of rest that the ultimate result would be that the day would be devoted to sports and to amusement and the public would follow their natural inclination in that direction. He contended that the moral laws given on Sinai were now in force and that the law that the Sabbath day should be kept holy was abrogated…..” (PARLIAMENT. The Argus: October 23,1874)

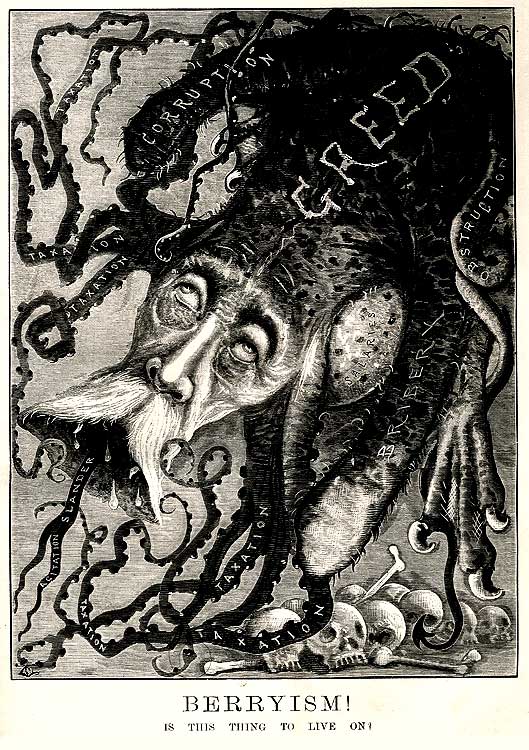

The Quennell’s eighth child, Henry Edwin was born in Richmond in 1876. Building trades were experiencing a slump after Premier Berry’s ‘Black Wednesday’ financial and political crisis in Melbourne in January 1878. The radical liberal Premier clung to office while the colony was gripped with class conflict, including huge torch-lit processions through Melbourne sponsored by The Age (pro-Berry) and The Argus (anti-Berry) – although, remarkably, there was almost no violence. Almost no legislation was passed and the administration ground to a halt as funds ran out. The brickies intended to strike for an

increase of wages, and a half-holiday on Saturday, but they had to abandon the idea. In the brickmaking districts things were looking gloomy. The Hoffman Patent Steam Brick Company at Brunswick discharged 20 men and stopped one of their machines. Prospects for bricklayers then improved with the decision to rebuild the ‘dingy sheds’ of the old Paddy’s Market area between Bourke and Little Collins St. and relabel it the ‘New Eastern Market’. Besides being used by day as a vegetable market…

increase of wages, and a half-holiday on Saturday, but they had to abandon the idea. In the brickmaking districts things were looking gloomy. The Hoffman Patent Steam Brick Company at Brunswick discharged 20 men and stopped one of their machines. Prospects for bricklayers then improved with the decision to rebuild the ‘dingy sheds’ of the old Paddy’s Market area between Bourke and Little Collins St. and relabel it the ‘New Eastern Market’. Besides being used by day as a vegetable market…

‘on other nights the place has been the resort of the worst class of loafers and vagabonds of both sexes’. ‘Mounted on furniture vans in those precincts our shabbiest demagogues have uttered the silliest opinions in the worst possible English’. (The Australasian Sketcher, April 13, 1878).

However by October the bricklayers were on strike again trying to gain their half holiday on Saturday from the employer, J.Nation & Co. On 14 November, William Quennell, still secretary of the brickies society, advised his bricklayers ‘

‘that the lock-out at the Eastern Market still continues, no settlement having been arrived at’. A few days later the victory was won with ‘the contractors having conceded the demand made by the men for the Saturday half holiday. Work has never been entirely suspended, a few non society men having been employed, but things will now go on as they did before the strike’. (The Argus, 18 Nov, 1878).

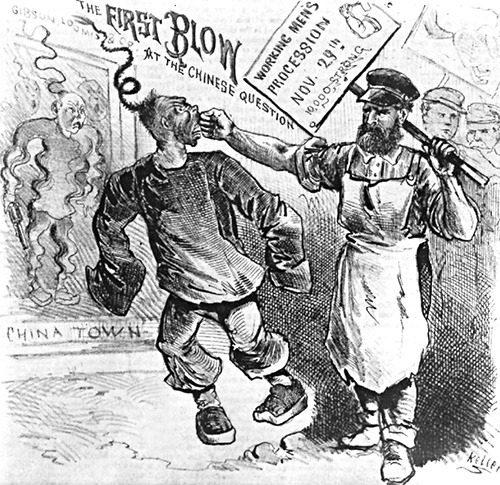

George Bowen Quennell, William and Mary’s ninth child was born at Richmond in February 1879. In 1879 the issue of employing Chinese labour, which had racist undercurrents going back to the gold rush days nearly 30 years before, came to a head as seamen in Sydney went on strike against the Australasian Steam Navigation Co. for employing Chinese workers.

On 3 January, William chaired a meeting at the Trades Hall “for the purpose of taking measures to prevent the introduction of Chinese labour”. It is embarrassing, as a relative of William, to report that he then addressed the meeting saying;

“They all knew that the presence of Chinese labour was a very great evil and that Chinamen were doing a very great injury both in point of trade and morals. It was well known that the Chinese used young girls for immoral purposes; and as regarded trade, they congregated in communities of 20 or 30, causing great loss to European working men”.

There followed differences of opinion about the way the Sydney seamen had conducted their strike by finally compromising with ASN Co. and the purpose of the meeting itself. William stepped down from the Chair insisting that the meeting should deal exclusively with “the question of preventing the introduction of Chinese into Victoria”.

Eventually Mr. J.C. Ryan moved

“That in the opinion of the various trades, it is desirable in the interests of the working classes an Anti Chinese League should be formed”.

William said he “would thoroughly support that motion, as it was for the purpose of forming such a league that he had attended the meeting”. He had “a great detestation of these men”, whom he “saw a great deal of at Richmond” and he “was convinced that it was high time to take steps to stop their further introduction into the colony”.

Mr. M.D. Miller also warmly supported the motion and said”that if proper steps had been taken in San Francisco and other parts of America long ago, the Chinese evil there would never have reached its present magnitude. They should take steps at once to prevent the evil establishing itself here”.

Australian Trade unionists closely followed American industrial activity and their model. This tendency became fossilised in the American spelling of ‘Labor’, in the eventual name of the Australian Labor Party. The Americans were moving to restrict Chinese immigration and Australian unionists were frightened of a flood of cheap asian labour and of the introduction of smallpox and leprosy by Chinese, as had happened in America, on top of their undeniably racist regard for ‘an inferior people’. These fears spread widely into the community and the ‘Anti-Chinese Question’ became one of the major issues of the period. It is interesting to note that the Australasian Steam Navigation Co. sea captains who worked with the employed Chinese liked them because of their “greater sobriety, willingness and civility” – not to mention only having to pay them about a quarter the wage of an Australian seaman. The seamen’s strike resulted in enormous impetus to the union movement in Australia as workers began to realise their power to effect issues by intercolonial and inter-trade co-operation.

This led to the First Intercolonial Trade Union Conference in Sydney in October 1879, which William attended as a delegate representing the Victorian Operative Bricklayers Society. At this conference resolutions were passed unanimously condemning the importation of Chinese workers and calling on the NSW legislature to restrict the immigration of Chinese by the imposition of a heavy poll tax.

Sir -Referring to a letter which appeared in your columns on the 4th inst. signed by ‘Tradesman’, I unhesitatingly state that most of his assertions are grossly untrue. He states that the secretary of the Bricklayers Society helped to establish an anti Chinese league without the society having been consulted. The statement is utterly false, the fact being that in response to a circular Messrs Griggs, Pilgrim and Quennell were appointed on behalf of the Bricklayers Society, which society in conjunction with others have contributed to the funds of the Victorian Anti Chinese League. In conclusion let me advise ‘Tradesman’ (of 20 years’ standing at the Trades hall) to in future speak the truth; also to sign his name so that his fellow tradesmen can deal with him as he deserves – I am, &c WILLIAM QUENNELL, Late secretary of Bricklayers’ Society, Trades hall. (The Argus, 15 February, 1879)

This grumpy and somewhat threatening letter from William indicates, by his sign off, that he is no longer Secretary of the brickies union.

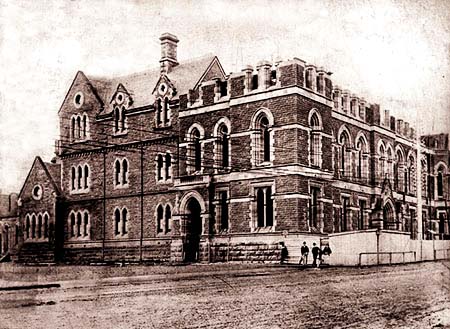

The next year (1880) Sir Henry Parkes, who also opposed Chinese Immigration, proposed an Intercolonial Conference to discuss the Chinese immigration question in general and to consider a draft bill with a view towards passing uniform legislation. Thus began the long history of Australia’s White Immigration Policy. (see “History of the White Australia Policy to 1920” By Myra Willard) Mary’s mother died in Surrey in 1880 while William and Mary’s tenth child, Albert Line Quennell was born at Richmond in 1881. One of the main principles of the 8-hour movement was that if working classes were given leisure time, they would have the opportunity to educate themselves. In 1881 the Honorable Francis Ormond, a noted Victorian philanthropist and member of parliament, suggested that a technical institute be built in Melbourne, offering further education for working men and women. He offered to donate half of the costs and the Trades Hall committed to providing the balance of the funds for the establishment of a ‘Working Mens College’.

In 1882 William was a Trades Hall candidate for election to a council to establish the Working Mens College. He was beaten in a hotly contested poll by two interesting Melbourne identities. One was David Syme who ran ‘The Age’ newspaper and came to have a very strong influence over the Victorian parliament and the other was C.J. Paterson, who became a well known decorator and landlord and patron to the artist Tom Roberts. The Working Mans College was eventually completed and opened in 1887. It was a great success and enrolments grew to over 2000 in the first 2 years with a curriculum including subjects from a variety of practical and vocational fields, from business, to engineering, to fine arts. This institution eventually became the Royal Melbourne Institute Of Technology (RMIT).

Back in Lambeth, Surrey, William’s father, William snr. died in 1882 and his mother, Julia, died in 1884. William and Mary’s eleventh child, my great grandmother, Olive Grace Quennell, was born in Richmond in 1883. Possibly because of the financial crash in Melbourne in the early 1890’s, William appears to have had a change of career from Trades Hall unionist to working for the Richmond City Council. From about the mid 1890’s till early 1900’s William placed several items in ‘The Argus’ advertising forthcoming Richmond Council Elections (including an ‘address to the electors’ by future Victorian Premier, James Munro) which are signed: Wm. T. Quennell, Hon. Secretary. In 1889 he presented a petition to the Richmond Council from 102 ratepayers requesting that Council not allow the Town Hall to be used for a proposed ‘Parnellite’ meeting. (ie. followers of Irish Home Rule Parliamentarian Charles Parnell)

William Thomas Quennell died on the 3rd April 1912, at his home, 7 Weinburg Grove, Hawthorn. Mary lived another 7 years after the death of William dying on the 3rd May 1919, at her home, 7 Wattle Grove, Hawthorn. They were both interred at ‘Boroondara’ Cemetery, Kew. The probate for both of their wills was granted jointly to their son Henry Edwin and to Joseph Black, the husband of their daughter Rosa Victoria.

The change of name of their street address from ‘Weinburg Grove’ in 1912 to ‘Wattle Grove’ by 1919 was presumably one of many changes made to German sounding names in Australia during and after World War 1. William and Mary are also recorded as living at 80 Mont Albert Road in East Camberwell. The Quennells were sufficiently sentimental to name both the Mont Albert Road and later, the Wattle Grove residences “Kennington”, undoubtedly inspired by the name of the lane in London where William grew up. The 80 Mont Albert Road house was probably built by William himself …with plenty of bricks of course!

It was described in the advertisement for it’s sale, 6 months after Mary’s death as:

“a Two storey BRICK residence, slate roof, containing 8 rooms, stables, etc. Land; 50ft. Frontage by a Depth of 150ft”.

This recent photo indicates the old 80 Mont Albert Rd homestead being extensively renovated in 2013.

Two of William and Mary’s daughters, Alice and Millicent, lived together for many years at 16 Orange Grove, Camberwell. They also named their residence “Kennington” and operated a dressmaking business in close-by Hawthorn together.

It has been a very engaging task piecing together what I can of the lives of my maternal great, great grandparent’s. I have had no letters, personal material or even family stories to go by.

I have felt a keen regret that generally only details of men’s public or working lives are available in the sources available to me ie. old newspapers, archives and books. The womenfolk only ever seem to get a mention in the Births, Deaths and Marriages columns while they continued with the important work of raising the children (13 in Mary’s case!) and supporting their families.

I wish I could know more of these women’s lives. I hope to trace an outline of what became of the 13 Quennell children on another page on this site!

Dear PJ, my name is Daniel Quennell. My father is Martin Quennell, and his father is Alan Ronald Quennell. Alan or Ron as he was more commonly known was the second child of Charles Clifford Quennell, Robert Clifford is the eldest, and Sylvia Quennell being the youngest to my knowledge. I am amazed at your work here, my family history on my father’s side has been so vague until this phenomenal site, so thankyou!

Good to know others get some benefit from my research. Cheers Daniel.

I too am a grand-daughter of Rosa Victoria Quennell. The story that was passed down our family line, was that Benjamin Bruce had been a foreman working for the Quennells. The story goes, that Mary, his daughter, used to bring her father his lunch every day.

On realising that she no longer came to the factory, William asked where she was. When he learnt that her family had gone to Australia, he pursued her to Australia and waited until she was of age to marry her. She married him 2 days after her 17th birthday.

I must admit I too am horrified at his racism, but in examining the history of Kennington and Lambeth it comes clear as to why he was so conservative.

I found it ironical and sad that he had joined forces with others to petition against a house in Erin St. Richmond being converted into a private hospital that catered for non-paying patients. This group were objecting on the grounds that it was catering for those who would not being paying as it would lower the value of their properties. This hospital it turns out was “Bethesda” and where my siblings and me were born and where a sibling worked for many years. How the wheels turn.

to ” pjp ” , regarding Collingwood supporters , my wife Heather is the daughter of Ruth Duncan nee Quennell , Heather and her Deceased brother Geoffery are and were avid Collingwood supporters , scandalous indeed.

Rod Watson , Albany WA

Hi Rodney,

I’d love to catch up with both Heather and her twin, Colin. My brother, Dale, and I were also twins born only a couple of weeks ahead of Colin and Heather. I’ve lost Colin’s contact details. Auntie Ruth used to arrange that Heather and I have stay overs together, whilst Colin and Dale did the same when we were young. (you have to wonder what was in the water in those days for that to happen as being conjugal twins it is not genetic.

I and my brother Steven are Quennell descendants from Alfred Sydney Quennell. Steve Gilbert would like to contact you, he has a lot of Quennell research.

Hi Morna,

you or Steve are welcome to contact me at

dooden66@gmail.com

in regard to any Quennell family research.

Cheers

I was interested to read this as I too am a descendent of William Thomas and Mary Bruce. I was in regular contact with Joan Quennell now deceased (an English descendent of William Thomas’ brother living in the UK). She’d been a Tory MP before retirement. I stayed with her at her property in Hampshire on several occasions and she also came out to Australia when we held a Quennell reunion. Joan provided me with considerable family history. I’d be happy to provide my summary should you be interested. It is possible you may have the wrong Quennell (Quinnell) re. the original migration to Australia as my records show William Thomas arrived 2/09/1853 on ‘the Asiatic’. According to my records he was a bounty passenger and worked as a carpenter on the trip out. The story was that he built a wheelbarrow and walked from Sydney to Melbourne carrying all his belongings. Should you provide me with your email address I’ll forward you what I have. Lyn

Hi Lyn, thankyou. Relevant information and any documentary evidence will be gratefully received at: dooden66@gmail.com

Cheers

Hi Lyn, I have just been given a photo of Rosa and Joseph Black by my father Lloyd Nixon as they are his grandparents. This led me to this page. I would be very interested in your family history records. Would you be able to email some information to me?

Dear PJ: I’m proud to be related to the Gillies!! Tx for explaining that connection. I’m the oldest son of Albert Quennell and Maidie Henry, born in Napier NZ, prep school Mbeya East Africa, public school Gordonstoun, MA from Lancaster U, MSc from London U. I was a career UN development manager, residing and working in various countries. and have been resident across the Hudson from Manhattan since 1983. email peterquennell@gmail.com if I can be of any help. Tx again! Peter Quennell.

Hi, I have recently bought some salesman’s button cards with glass buttons. They look to be of some age..maybe nearly 100 years old. They have a label on them which says H.E Quennell and son, Flinders Lane Melbourne. I can’t find any info at all on this name and would appreciate any information that may give me some insight into their history. Thank you

Hi Edith,

Henry Edwin was the Quennell’s eighth child as mentioned in the story above. I have some further information on Henry – if you post an email address I can send it to you. Cheers

The house that their daughters Alice & Mill Quennell lived in Orange Grove, Camberwell was also named “Kennington”. Carrying on the family tradition??

It’s interesting that Alice was born in England while her long-time companion and younger sister Millicent was born in Australia. As you point out joj, the family obviously had a strong tradition of not forgetting their ‘mother’ country – they all lived in a ‘Kennington’ – or two!

You weren’t tempted to “blur” history and omit the detail of where William and Mary were married and had their first child, were you, pjg? I mean, talk about dredging up embarrassing – scandalous, even – family indiscretions! Collingwood! Oh well, at least it wasn’t Carlton.

The temptation certainly arose David, but one can’t change history! There is, I’m pleased to say, no evidence that any of their family took the ultra embarrassing step of becoming actual Pie supporters! Only one person in the whole history of this family has taken that woeful step – and my sister shall remain anonymous!