My maternal family lineage goes back from Melbourne to ‘Migans’ and ‘Frasers’ on Waiheke Island, New Zealand then further back in time to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia and ultimately to Ullapool and Assynt in Scotland. How my ancestors journeyed from Scotland to New Zealand under the leadership of the astounding clergyman Norman MacLeod is told below. This story originally appeared in the ‘Clan MacLeod Magazine’ in 1980-81 (see links below). It is extremely well researched and I could not improve on it so it is reproduced here with thanks.

Rev. Norman MacLeod in Scotland

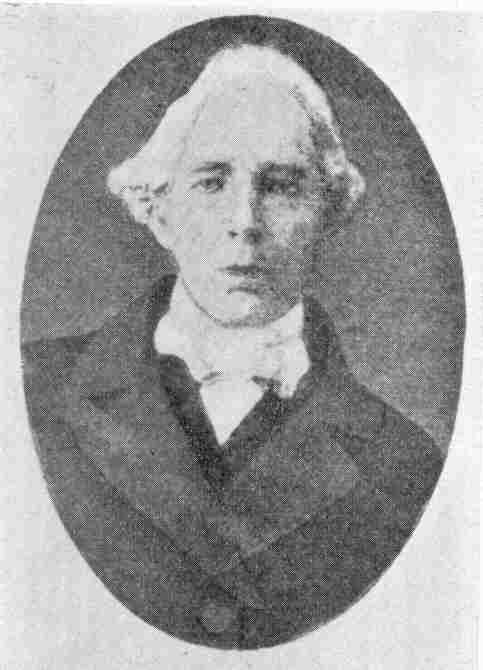

Rev. Norman MacLeod

Norman MacLeod was born at Clachtoll in Assynt on 29th September 1780. Nothing now remains of the house where he was born or the village where he lived, except the shattered stump of the prehistoric fort perched in decaying piles on the sea shore. The village was situated on green grassland between the golden white sand beaches of clachtoll and Stoer. Now only the dilapidated drystone walls and rickles of purple stone amongst the grass and clover define the old boundaries.

Beyond the sweetening effect of the sand, the ground rises in irregular lumps of grey rock, sparsely crowned with sour grass and heather. Ten miles inland to the east loom the snouts of Quinag, Canisp, Suilven and Cul Mor, riding like galleys against the gales.

The MacLeods of Assynt

According to MacLeod historians, at least, Assynt passed peacefully to the MacLeods of Lewis about 1340, when Torcall, 4th Chief, married the Assynt heiress, Margaret MacNicol. A few years later ‘Torkile MacLode’ certainly received from King David II a charter for ‘Asseynkie’. About a century later Assynt was given to Norman, second son of Roderick, 6th of Lewis. In an age of violence and uncertainty, the MacLeods of Assynt were as violent as their neighbors. By the end of the century, when old Roderick, 11th and last of Lewis, was leaving his disputed possessions to his fractious heirs, and Rory Mor, 15th of Harris, was succeeding his nephew at Dunvegan, Donald Ban MacLeod seized Assynt from his cousins. Though he brought stability to the area he also brought the seeds of the MacLeod’s destruction. In 1596 Donald Ban received a charter for Assynt from the increasingly powerful MacKenzies, who in 1610 seized Lewis. They were soon looking covetously at Assynt and mounting debts and legal intrigue spun a tightening web. The MacKenzies raided Assynt and in 1547 Donald Ban died.

According to MacLeod historians, at least, Assynt passed peacefully to the MacLeods of Lewis about 1340, when Torcall, 4th Chief, married the Assynt heiress, Margaret MacNicol. A few years later ‘Torkile MacLode’ certainly received from King David II a charter for ‘Asseynkie’. About a century later Assynt was given to Norman, second son of Roderick, 6th of Lewis. In an age of violence and uncertainty, the MacLeods of Assynt were as violent as their neighbors. By the end of the century, when old Roderick, 11th and last of Lewis, was leaving his disputed possessions to his fractious heirs, and Rory Mor, 15th of Harris, was succeeding his nephew at Dunvegan, Donald Ban MacLeod seized Assynt from his cousins. Though he brought stability to the area he also brought the seeds of the MacLeod’s destruction. In 1596 Donald Ban received a charter for Assynt from the increasingly powerful MacKenzies, who in 1610 seized Lewis. They were soon looking covetously at Assynt and mounting debts and legal intrigue spun a tightening web. The MacKenzies raided Assynt and in 1547 Donald Ban died.

He was succeeded by his young grandson Neil, 10th and last of Assynt. Stigmatised unjustly for the capture of Montrose in 1650, Neil became engaged in a legal battle over Assynt. He had first his charters, and then his lands stolen by the MacKenzies and by 1672 they were in full control, adding Assynt to their wide possessions in Ross–shire.

Support of the Stuart cause had stripped the MacKenzies of much of their wealth and influence and by the end of the 18th century, Assynt had been purchased by the Marquies of Stafford to add to his wife’s huge Sutherland Estates. To this day Assynt still forms part of Sutherland District.

Norman’s Early Life

Little enough is known of Norman MacLeod’s parents. His father was probably the tacksman at Clachtoll, trying to keep up the appearances of a gentleman on the fringes of the MacKenzie lands. Norman received an eduation probably at Lochinver, the principal village on the Assynt shore, tucked snugly into the protective depths of the sea loch, and five miles south of Clachtoll. Norman remained in Assynt, where he was probably a farmer or cattle drover, for he later referred to a man who bought three cows from him and never paid for them, and received encouragement from a MacDonald who was tacksman of Lochinver. He married the tacksman’s relative, Mary MacLeod. He may also have been a fisherman.

Assynt, Scottish Highlands

It was an unsettling time for intelligent young men. Everywhere in the Highlands the landlords were talking of ‘Improvements’ and brave soldiers for the war with France. The people were emigrating when they could. The ministers of the church were living comfortably in their spacious manses while the people went hungry. In 1800 the first clearances in Sutherland took place in Strath Oykell, not far from Assynt. In 1807 ninety families were removed from the Sutherland parishes of Farr and Lairg.

University

In the autumn of 1808 Norman began to study for a Master of Arts degree at Aberdeen University. Norman came late to his studies, for he was twenty–eight. Perhaps his ability to communicate to others had decided him to become a schoolmaster or minister of the church. Four years later in 1812 he graduated, winning the gold medal for moral philosophy. Norman then moved south to Edinburgh where he began to study theology. He remained in Edinburgh for two years, and though one story claims that he was thrown out for criticizing the morals of his professors, it seems more likely, from his later conduct, that he gave up all thoughts of the ministry because of the corrupt state into which, he considered, the Church of Scotland had sunk.

Norman returned to Assynt with a degree but no license to preach. The parish had been transformed. In 1809 Patrick Sellar took employment with the Marquis of Stafford and there were widespread clearances in the Sutherland parishes of Dornoch, Rogart, Loth, Clyne and Golspie. In 1812 he cleared Assynt.

The people were leaderless. Their chiefs had become money hungry landlords living in London. The tacksmen had been replaced by lowland sheep farmers. The ministers preached that the people should accept their misery as God’s just reward for their wickedness.

In 1813 clearances began in Kildonan and the following year is still remembered as the ‘Year of the burnings’ when Patrick Sellar stripped Strathnaver of its people and burnt their mean houses to the ground. For this work Patrick Sellar was brought to trial for manslaughter and acquitted by a jury of fellow improvers.

During these troubled times Norman had begun preaching. He conducted services in Assynt, which attracted many people. This brought him into direct conflict with the minister, Rev. William MacKenzie, whom Norman considered to be unworthy of his office. Thus began Norman’s life–long opposition to the ministers of the Established Church of Scotland.

Rev. John Kennedy, son of the assistant minister in the parish, later wrote of Norman:

His power as a speaker was such that he could not fail to make an impression, and he succeeded in Assynt and elsewhere, drawing many people after him. His influence upon those whom he detached from a stated ministry was paramount, and he could carry them after him to almost any extent. Some of the people of Assynt were drawn into permanent dissent. Some, even of the pious people, were decoyed by him for a season, but eventually escaped from his influence.

Ullapool

It is said that Norman then moved thirty miles south to the fishing village of Ullapool which had been established in 1788, and started a school. There had been a school, however, funded by the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge, since 1800. From 1st May 1814 to 1st May 1815 the school teacher was Donald Cameron, who received a salary of £20 and was attested by the minister of the parish of Lochbroom. In April 1816 Donald Cameron was described as ‘late Society Schoolmaster at Ullapool’, but no salary was paid to any schoolmaster from 1st May 1815 to 1st May 1821.

Norman is nowhere mentioned in the Minutes of the Society, but he may have become schoolmaster on 1st May 1815. He is said to have had one hundred pupils and was to have received his salary partly from his pupils’ fees, and partly from the Society, through the parish minister.

Rev. Thomas Ross, though engaged in translating and publishing the first Gaelic Bible, was thought of no more highly by Norman, than had been William MacKenzie. Norman refused to attend Rev. Ross’s services, which were held in the parish church some miles away, and he conducted services of his own, which were well attended, in the school house. For a year Norman was in open defiance, for it was illegal for an unlicensed man to preach. Norman was called before the Kirk Session and there followed an heated debate.

Rev. Ross offered a compromise, stating that he would be satisfied if Norman attended church ‘now and then, even rarely, say once in a quarter, and show otherwise by your conversation and conduct your approbation of my ministry’, and allowed him twenty days in which to consider the offer.

Norman refused to compromise and was forced to surrender the school, though no–one was to fill the vacancy for six years. Norman remained in Ullapool for a while, preaching on the Sabbath day without payment. Rev. Ross brought charges against him, but the charges were dismissed. Norman was later to write, ‘probably I should never have come to Nova Scotia but for the prosecution if not the persecution of that man’.

When the fishing fleet moved round the north coast of Scotland, Norman followed and ‘served for a season in the troublesome and dangerous Caithness fishings.’

Emigration

Norman MacLeod at thirty–seven, unable to farm; well educated, but unable to teach and forbidden from preaching, had reached an age when he should have been settled into his life’s work. He had no alternative but to emigrate.

Alexander Mackay, Waipu, son of Duncan Ban, and married to Norman MacLeod’s granddaughter Maria Ross, later wrote that the emigrants from Scotland

were all what is understood by the term “well to do” people and could have made a comfortable living in their native land. But they, as a rule, had families, they had rent to pay for their farms, they did not own them and they had no chance of ever doing so. They were enterprising and knew that by going to North America they could become owners of land by settling on it and cultivating it. Besides, there was plenty of room for themselves and their families, clear of the exactions of the landlords.

Norman left Lochbroom on 14th July 1817 in the barque Frances Ann, with more than 400 men, women and children on board. Even his voyage was eventful for in mid passage the ship ran into a storm, and when the captain and crew decided to return to Scotland Norman informed them

that if they put back, some way or other he would be saved, but no other one on board the ship would ever see land. Fortunately for everyone concerned the storm abated and the ship sailed on to Pictou Harbour, Nova Scotia. Shortly afterwards, Mr. MacLeod settled in the vicinity of West River, Pictou County.

Ullapool was created in 1788 as a fishing village on a spit of land sticking out into Loch Broom. Norman MacLeod taught in the S.P.C.K. School here in 1815-16, and emigrated from here in 1817. The village is still a busy fishing centre. The car ferry to Stornoway, Suilven, is named after the mountain in Assynt. Photo: RHM.

http://www.broadrunit.com/RootsWeb/NormanTint51.html

Rev. Norman MacLeod in Nova Scotia

In the late summer of 1817 Norman MacLeod and 400 other passengers arrived at Pictou Harbour, Nova Scotia, having sailed from Scotland on the barque Frances Ann. They immediately prepared to face the difficulties and the hardships of all pioneer settlers. The settlers found that the shorelands had all been previously appropriated, however they were able to secure land in what is known as the Middle river area, between Alma and Gairloch.

Norman had by now become a leader of this people. They trusted him absolutely in secular and practical as well as in spiritual and religious matters, and followed him faithfully. Pictou was booming, lumbering was flourishing, Pictou ships carried on a year–round trade with various parts of the new world, rum was available in plenty from the West Indies, and the small town was rather a boisterous place. By MacLeod’s standards this was not a sufficiently hallowed spot.

In the second year of the Middle River settlement Norman was joined by his wife and family from Assynt, and about the same time he received an urgent and pressing invitation to join a colony of highland refugees who had settled in Ohio. Norman called his people together. The younger members of the community were almost unanimously in favour of the change, and finally it was decided that most of those who had come from Scotland in the Frances Anne should go to Ohio.

To Cape Breton on the Ark

This meant that a ship had to be built. The keel of the vessel was laid at Middle River Point in 1819 and all through the summer, autumn and the following winter the work of building went on. The people around who were not ‘Normanites’ named the ship Ark and its designer, Noah. In spite of ridicule, and numerous difficulties incident to such an enterprise, work went steadily on so that by May 1, 1820 a well built ship of some 18 tons was ready to embark. This small schooner was designed to take only the first advanced party with the remainder to follow when a settlement had been established.

There are numerous conflicting stories about Norman and his exploits. One had to deal with the sailing of Ark to Cape Breton. Some writers suggest that on rounding Cape Canso and moving out into the Atlantic he encountered terrific gales from the south west and, to avoid danger, he took shelter in St. Ann’s Bay in comparatively smooth water. It is more likely, however, that on this reconnoitering trip he anchored overnight in St. Ann’s Bay, Cape Breton.

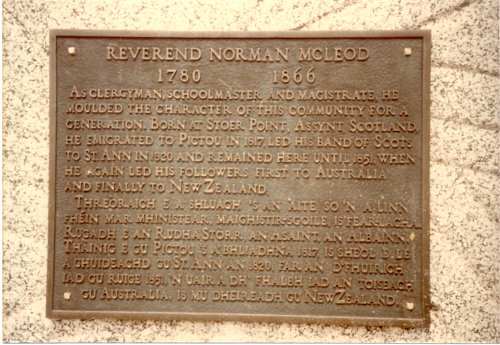

MacLeod monument in St.Anns

Norman and his followers were enchanted by the beauty of the place, reminding them so much of the highlands of Scotland from whence they originally came; the waters being alive with fish, sunlit beaches, and silent forests, that to these mariners recently exposed to the boom town of Pictou this was a most desirable spot. All thoughts of Ohio were quickly removed.

Eventually the rest of the settlers and their families arrived. They took up blocks of land near the entrance of the harbour where Englishtown is now, and then up to the mouth of the North River. They built a vessel in which they traded up and down the shore and secured supplies. Their Pictou experience of woodcraft and of making clothing from skins and in working the soil helped. They also fished and hunted. Norman’s spacious cabin, at the head of the harbour called South Gut, where he established himself on a block of land about two miles square, was not only used as a home for the family but also at first as a school and church. It was early agreed that Norman’s land should be worked by the community, and he himself left free to devote to teaching and preaching.

By the end of the year a separate and suitable church and school were erected at Black Cove, near Norman’s home. Gradually the forest was pushed back, and the land produced potatoes, oats, wheat and vegetables. Each family ground its own meal with a small hand mill, some cattle were secured, and the close knit community began to grow. By 1825 the entire people had abundance of food, clothing and shelter and educational and spiritual facilities. Greater numbers came to settle from Scotland to join with Norman and his pioneers.

Ordained by the Church

In 1826 Norman paid a lengthened visit to a clerical friend, a Rev. Mr. Denoon, in Caledonia, New York. It is reported that he was introduced to the local presbytery, which, after some months of training and being satisfied as to his character and previous education, granted him the Presbyterian license to ordination to the ministry. Returning to St. Ann’s his people received him with much joy.

By now hundreds of fellow countrymen had arrived from Lewis and Harris, settling all along the North Shore to Cape Smokey, and south towards Baddeck. Seeing that the local presbytery was unable to supply the people with religious ordinances, Norman offered to preach to them. Although he was now ordained and acknowledged as a clergyman, he was not associated with the Presbyterian or any other organized church in the Province.

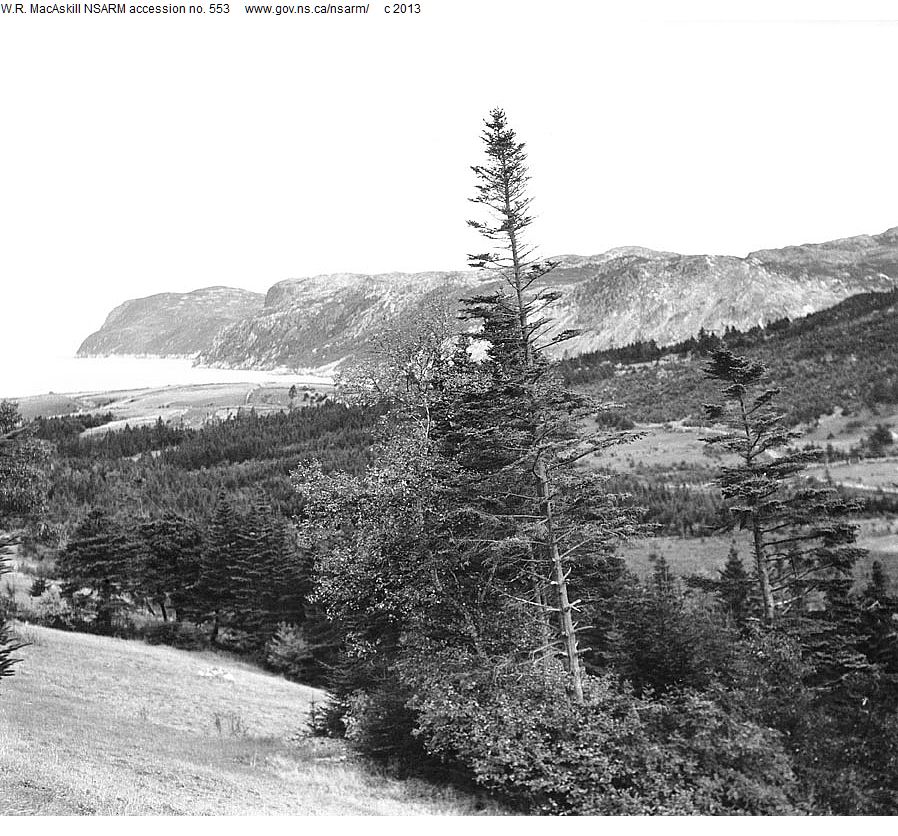

Cape Breton landscape

All violations of the civil and moral law were duly enquired into and punished. He denounced sin and sinners from the pulpit so that he truly became a terror to evil doers. He was a total abstainer. Under his patriachal rule the people of St. Ann’s became distinguished for their intelligence and rectitude. As early as 1840 he formed a branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society. The government of Nova Scotia appointed him a schoolmaster, postmaster and justice of the peace, thereby giving him official status and further greatly increasing his growing influence and prestige.

By 1846 so popular had he become, and so appealing was his preaching, that the original church built in 1821 would not accommodate his people and a new edifice was erected at the Cove, capable of seating 1,500 people. Hardly had the church been completed than trouble had arisen in the community and disintegration had set in. Many objected to the minister’s rigid control of their private life. A possible measure of jealousy on the part of other would be community and clerical leaders, seems to have played a part. The community became sharply divided into Normanites and anti–Normanites.

Hero–Tyrant

The obedience and submission demanded of the Normanites had over 30 years enabled him to exercise almost absolute power. Some fancied slight would drive some of the members of his church away and be completely ostracized. It is reported that every one of his friends who had formed the original nucleus of his colony, and who had followed him from Scotland and from Pictou, would eventually all be ostracized by him and under circumstances of great malice.

A sample of Norman’s sharp tongue survives in this letter to an old college friend:

You were never by nature but a mere simpleton, or two–thirds of an idiot, and your false conversion, scraps of philosophy, fragments of divinity, painted parlour, dainty table, sable surtout, curled cravat, ponderous purse, big belly, poised pulpit, soft and silly spouse, the acclamation of fanatics and formalists, the association of kindred plagiarists and imposters, your seated conscience and a silent God have all conspired, no wonder, poor man, to turn your mind to total forgetfulness and your head to eternal dizziness.

Obviously, with words such as these in his everyday speech and preaching, his churchgoers would not be disappointed with the fire and eloquence of his sermons.

Norman had a poor opinion of a great number of his fellow men, and his narrowness of view was extreme. For example, he prohibited women from wearing ribbons and the like. He seldom baptised and there is no record of him having administered the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. For revival meeting he reserved great denunciations

some are screeching screaming — others are peeping and tooting — or snuffling and snorting — and that truly in a mood far beyond the utmost ordinary pitch of their pulmonary power, others falling down prostrate, monkey like spring from place to place with suprising ability. Another sort sit still, statue like, in a wild and vacant gaze.

Norman spoke both English and Gaelic, although he conducted all classes in the latter language. As a teacher he is reported to have done excellent work. Most of the successful early teachers of the area had received their education from him. As Flora MacPherson’s book records ‘his teaching in Gaelic was an important factor in the maintenance of a continuing Gaelic culture in the St. Ann’s district for many years. The language had not only persisted but continued in a much purer form than if it had been passed on orally and picked up only from home use.’

It was as a law giver and interpreter of the scriptures that he became noted for considerable harshness. It was in Cape Breton that he wrote and published a volume of some size titled ‘The Present Church of Scotland and a Tint of Normanism’. It was written in response to requests from some of the regularly ordained ministers resident in Cape Breton asking by what authority he called himself a clergyman.

A born leader, with great courage, characterized by the harshness of his rule, loved by many, resented by some, his discipline was no doubt suited to a time in which he lived. Only those who were tough, strong and well disciplined could survive the pioneer environment.

Norman’s wife Mary had borne ten children. Mary was in poor health most of the time, worn out by living in a succession of pioneer places, and emotionally exhausted by the strain of living with such a man. None of the sons apparently turned out well. It was whispered in the community that he turned a blind eye to conduct in his own children which he would strongly denounce in others.

As the community had grown, a desire for trade, and the prospect of money and wealth had taken root especially in the minds of many of the young who had grown up in the 30 years of the community’s life. A trading scheme was eventually resolved upon, which proved a failure and a means of further disintegration. A ship was built, loaded with surplus produce of the land and the forest and sent off to Glasgow, Scotland, with the expectation that the vessel would return with substantial sums in payment. One of Norman’s sons, Captain Donald, was put in charge of the ship and of the enterprise, but it proved a failure. Neither ship nor captain ever returned, and no monies ever reached St. Ann’s.

New Zealand

In 1848 there was a disastrous crop failure, and the government had to supply food to avert starvation. Shortly before this, Norman had received a letter from his son, Captain Donald, the first in eight years, which startled St. Ann’s to learn that the prodigal son was now in Australia, to which place Donald had worked his way after the failure of the business enterprise, and the sacrifice sale of the ship and the cargo in Glasgow. A consensus eventually developed in the community to leave the cold and bleak shore of Cape Breton and set out for the wonderful land of sunshine and promise in the midst of the southern seas. It was a land they observed that knew neither frost nor snow. Its climate was genial, its soil rich and prolific, with abundance of gold in its rocks and rivers, nuggets having been found on the surface as large as a man’s head.

Norman was now almost 70, and one would suppose his appetite for adventure had been satisfied. But local conditions had not been developing satisfactorily lately. With the severe potato blight some of the young had become restless and were leaving, so the old patriarch called his friends together to seek divine guidance. He himself believed that the call had been from God, and many of the people considering the circumstances looked upon the matter as a plain and direct imposition of divine providence.

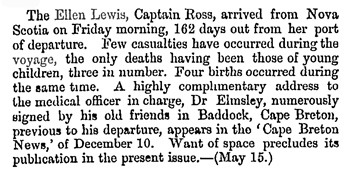

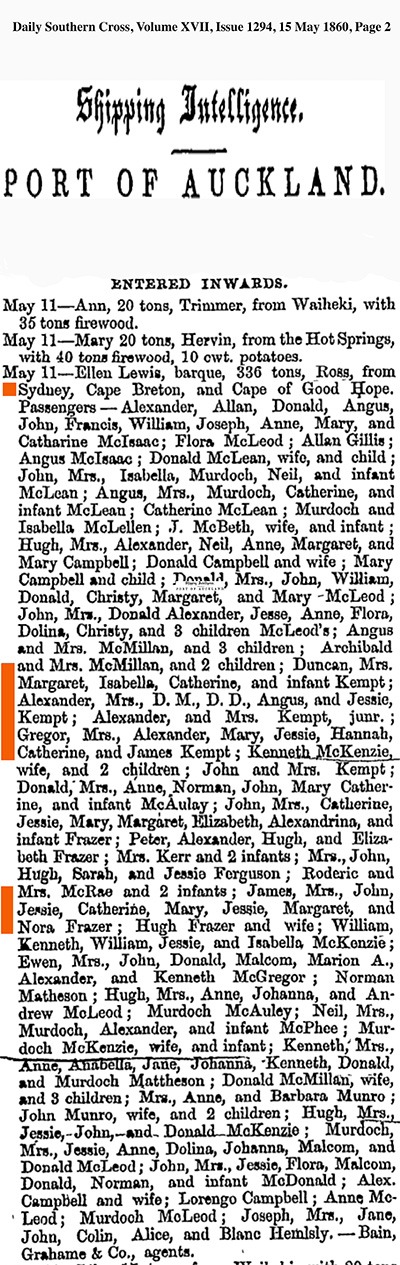

The picturesque migration from one side of the world to the other was made in six ships, namely Margaret, which was the first, and took Norman and 130 others; Highland Lass, with 188; Gertrude, with 176; Spray, having 66; Breadalbane, 129; and finally Ellen Lewis, with 188. There were 877 and the last in December, 1859. In size the vessels ranged from Spray of 99 tons to Ellen Lewis of 336 tons. They were all sailing vessels, the sailing time being from five to seven months for more than twelve thousand miles. There was no Panama Canal, so the Cape of Good Hope had to be rounded. It is a tribute to their navigating ability and their seamanship that not a ship nor passenger was lost.

With their usual spirit and courage they built, provisioned, and sailed their ships and themselves first to Adelaide, where Donald MacLeod could not be found, then to Melbourne where he was unknown, and finally on to New Zealand where they settled under their beloved and trusted leader.

On the hillside above Black Cove, Norman MacLeod preached his final sermon on that autumn day well over a century ago. On the hillside was assembled every one who could make the journey. For most of them who were staying behind, it was to be a final parting. Norman stood facing his enormous congregation, with Margaret swinging impatiently at her moorings on the sunlit waters below. This was Norman’s greatest sermon, those who were sailing to the new land were dedicated to the pilgrimage, and those who stayed behind were comforted and challenged too. His voice was breaking with emotion at times, he presided in his usual black gown, in the service which was his leave taking from the people of St. Ann’s.

Rev. Norman MacLeod in New Zealand

The Rev. Norman MacLeod, at the age of seventy-one years, led his people from St. Ann’s Cape Breton Island, forth again into the wilderness. Perhaps he did not think of it as “the wilderness” having learnt much about Australia from the letters of his son Donald who had written good accounts of the availability of land and the opportunities there. Donald was at Adelaide and this destination was Norman MacLeod’s first intention.

The reasons for leaving Nova Scotia were a shortage of suitable farming land for growing generations; American fisherman were competing for the harvest of the sea in the waters where St. Ann’s men fished, and, 1848 was a disastrous season with ruined wheat and blackened potato crops.

So, with much prayer and deliberation, Norman made the fateful decision that it was better for his people to go forth together, than scatter and lose their identity. Once the decision was made energetic preparations began — extremely self–sufficient and self–reliant preparations. Over the next two years ships were built in one of their own shipyards, provisions were obtained from their own fields and fisheries, experienced captains and crew chosen from among themselves, and among the intending emigrants most essential trades were represented. Because of their successful thirty years in Nova Scotia there was no desperate shortage of money either.

In 1851 Norman MacLeod, at the age of 71 decided to lead his people from St. Ann’s, Cape Breton, to a new homeland.

“Margaret” Sails

On 28th October, 1851, the pioneer barque, Margaret, with one hundred and thirty passengers, including the Rev. Norman and his family, left St. Ann’s, Nova Scotia, for Australia. The Margaret arrived in the Spencer Gulf of South Australia on Saturday, 10th April, 1852. It looked a rather uninviting land being in drought conditions at that time. The capital, Adelaide, was some miles away up the Torrens River. Sunday was spent on board and a service of Thanksgiving for their safe arrival was held. Donald had left word that he had gone to Melbourne, and by the beginning of June they were at Melbourne too. Gold had been discovered and to the settlers, the way of life in this struggling town seemed bewildering and distasteful. Some of the men tried their luck on the goldfields, or tried for work at carpentering or other trades. Insanitary conditions prevailed and a scourge of typhoid fever broke out; three of Norman’s sons died within a short period. It must have been a severe blow and caused him perhaps to question his wisdom in bringing his people away from Nova Scotia. The result was that he determined to leave the evils of the town. His people were really looking for timbered coastal lands suitable for farming development. While in Adelaide the Minister and his friends had heard reports of the Colony of New Zealand, and Sir George Grey had left from there to become Governor of the Colony. Norman wrote to him early in 1853 asking if he would make a special settlement for them in New Zealand.

In the meantime the brig Highland Lass had left Bras d’Or on 17th May, 1852 with 188 people and had arrived at Adelaide on 23rd October 1852, under Capt. M. McKenzie, and, before being sold, had made some profitable voyages on the coast, and had established contact with their friends at Melbourne. They agreed wholeheartedly that Australia was not the land they were seeking.

New Zealand

Norman received a favourable reply from Governor Grey, so Gazelle, a sturdy schooner already in the trade across the Tasman Sea, was bought by the McKenzies and the first party sailed on 2nd September, 1853, from Adelaide and arrived at Auckland, New Zealand, fifteen days later. In the issue of the newspaper ‘New Zealander’, in the shipping notes, it was reported that “the schooner Gazelle has brought a number of immigrants who, we trust, will prove a valuable addition to the population.” The Gazelle went back and forth across the Tasman bringing more and more of the Nova Scotian settlers each time and before long Norman was preaching at St. Andrews, being established in 1847, is known as the “First” Church.

On the first trip with the Nova Scotians, Gazelle sailed down the east coast north of Auckland and all eyes were on the land. They saw a beautiful coast–line with forest in the valleys, and on the hills, deep bays with rising land, not too steep, sunshine and mild weather. Immediately they decided not to look further.

Whangarai Heads, near Waipu, New Zealand

It took a year’s negotiations, first with Governor Grey, and then with Governor Wynyard who was not co–operative, and it was not until February, 1854, that they became first applicants for the land, still to be bought from the Maoris. The new settlers were willing to pay ten shillings an acre, the recognized price, but they did not have enough capital for an adjacent block for later arrivals. A Scot, who had been settled at Auckland since before 1840, having come at the age of twenty–three, and succeeded in making a fortune, proved a staunch friend, lending the money without security. He was a qualified physician, and a business man, became Mayor of Auckland, was a benefactor to the City which he loved, and is historically known as the “Father of Auckland”. He was Sir John Logan Campbell.

Settlement At Waipu

It was not until 1858 that the land situation clarified. There had been lengthy court proceedings brought by the British Resident, Bay of Islands, who claimed he had bought the land from the Maoris, and he sued Duncan McKenzie for trespass. He could not prove this, so his claim failed. In the meantime, more and more ships were arriving with the remainder of those Scottish Nova Scotian people who wished to settle in a new land under the guidance of their esteemed leader, the Rev. Norman MacLeod. By 1860 when he was nearing eighty years of age and the migration was completed, the total number who came was eight hundred and seventy–six men, women and children. All ships except Highland Lass had one or more MacLeod families on board.

It was not until 1858 that the land situation clarified. There had been lengthy court proceedings brought by the British Resident, Bay of Islands, who claimed he had bought the land from the Maoris, and he sued Duncan McKenzie for trespass. He could not prove this, so his claim failed. In the meantime, more and more ships were arriving with the remainder of those Scottish Nova Scotian people who wished to settle in a new land under the guidance of their esteemed leader, the Rev. Norman MacLeod. By 1860 when he was nearing eighty years of age and the migration was completed, the total number who came was eight hundred and seventy–six men, women and children. All ships except Highland Lass had one or more MacLeod families on board.

The blocks of land selected were in Northland, about one hundred miles north of Auckland. The main settlement was at Waipu (pronounced why—po) which one authority says means “reddened water”. This block was 66,000 acres, and there were others, mainly family blocks, at Leigh, Mangawhai–Kaiwaka, Whangarei Heads, Kauri–Hikurangi, and by 1864 Okaihau. They were all pioneered by these colonists.

In this, their last home, they found the two elements on which their initial efforts were concentrated — the forest and the sea — and they were vital to their survival. From the forest came the timber for coastal ships, and fishing smacks, which they built, also their houses, barns, and sheds, fencing and winter fuel, and a prosperous trade in surplus timber. By prodigious labours they cleared the flat land for cropping, turning the earth with spades. Their energy and self–reliance turned “the wilderness” into “the promised land”. Norman MacLeod’s precept and his example had shaped this community, and their everyday Christianity gained the love and respect of all who met them or had dealings with them.

Church and School

The first community project of the Waipu settlement was the building of their Church, to be followed by a school — the heart and the lungs of the community. On a ten acre site, the Church was a forty–foot by thirty–foot building of pit–sawn timber, all materials being donated or met by subscription. It was erected by voluntary labour, and opened debt–free. Norman ministered here until his death in 1866, and, as long as he lived, the people of Waipu were content to follow the lead and remain independent in their worship. He was sometimes stern and forbidding in the pulpit, and would publicly rebuke those among his flock whom he considered deserving of it, even his best friend, but he bore no malice and could, among his people afterwards, be kindly and generous with simple words for the children. A lady remembered him when he was over eighty and still preaching. She was a small girl, and recalls that “he gave us a dressing down,” but, she added, “he was most friendly afterwards.” The Minister expected that the women of the community should be simply and modestly dressed, especially for Church and was known to publicly rebuke any who appeared in a fancy new bonnet or a fashionable dress.

He had also been appointed a Magistrate and after his death the Magistrate from Whangarei visited Waipu when necessary, but so lawabiding were the settlers that his presence was rarely required there.

Norman realised the strength of the cultural bond of the language and saw to it that the Gaelic tongue did not die out. As far as possible, he insisted that it be spoken at social occasions, and at Church, where he conducted two services every Sunday, one in Gaelic and one in English. He was fluent in both languages. He never lost the respect of his people and his standards of honesty and fearlessness were to leave their mark on the generations following.

One hundred and twenty years and several generations later, the descendants of the Waipu Highlanders, as they became known, have spread to areas all over New Zealand, from North Cape to Bluff, and one is liable to meet, at any time, a New Zealander who says with pride, “My ancestors were Waipu Scots.”

A Masterful Man

What kind of a man was Norman MacLeod? He is still remembered over one hundred and twenty years later, in Scotland, where he was born, in Nova Scotia, where he spent the years of his maturity, and in New Zealand, his final resting–place. A contemporary of his years in Scotland wrote

Norman MacLeod had all the necessary characteristics of a Highland Chief — a fine personal appearance — was tall, stout and strong — and was kind, generous, patronising and paternal to his friends, but, at the same time, he was stern, haughty, autocratic and implacable to his enemies. In short, a masterful man of the stamp that a Celt is ready to admire, adore, obey, and follow at almost any sacrifice. In those days before the migration to Nova Scotia in 1817 he was monarch of all he surveyed, his personality overshadowed everything. His will was law to his people, and he was responsible to no–one but God and his own enlighted Christian conscience. All his influence he devoted, not to his own personal welfare, comfort, or aggrandissement, but to the intellectual, social and religeous welfare of his people. He was more than esteemed and loved, in a sense he was adored and idolised.

Both the people of Assynt and of Nova Scotia afterwards put their trust in a remarkable and versatile man, an accomplished and versatile speaker, a prolific writer, an excellent scholar, yet an able farmer, and a born leader. For nearly thirty years in Nova Scotia, Norman was the acknowledged leader of a hard–working community of lumbermen, shipbuilders, fishermen, farmers and traders, with freedom to own land and choose the Minister under whom they worshipped. He was not only their religious leader, but was also school–master and Justice of the Peace.

“Prophet, priest and King of Northland” is one description from Nova Scotia. Pictures of Norman in New Zealand show a stern, powerfully built man of arrogant eye and hard mouth. There are many stories about him, too, some idolising him, some critical; it seems he could arouse fanatical devotion or positive dislike. But these do not show the power of this man, who, by his own example and compelling argument, fostered simple Christian virtues. Even one of his critics had said that he was “a big man of leonine countenance; a giant mentally and physically.”

He was laid to rest on 14th March, 1866, in a spot twelve thousand miles from his birth–place, in a quiet country Churchyard with a vast panorama of sea and open country.

It can be truly said that Norman accomplished what the newspaper ‘New Zealander’ had hoped — he led to our country “a number of immigrants” who proved to be a valuable addition to the population.”

- A Tint of Normanism in Scotland Clan MacLeod Magazine Vol. 8, No. 51, Autumn 1980

- A Tint of Normanism in Nova Scotia Clan MacLeod Magazine Vol. 8, No. 52, Spring 1981

- A Tint of Normanism in New Zealand Clan MacLeod Magazine Vol. 8, No. 53, Autumn 1981

- http://www.broadrunit.com/RootsWeb/NormanTint.html

Daily Southern Cross, Volume XVII, Issue 1297, 25 May 1860

Great, great, great grandfather John Fraser arrives in Auckland onboard ‘Ellen Lewis’ with wife Mary Kempt and their daughter Catherine. Daily Southern Cross, Volume XVII, Issue 1294, 15 May 1860