Wilfred Bruce Quennell was born 20 August 1894 at Hawthorn in Melbourne. He was the son of WIlliam Bruce Quennell and Emily Innes and the grandson of WIlliam Thomas Quennell and Mary Bruce. In about 1904 Wilfred’s parents decided to move with their four young children (Edith 9, Wilfred 7, Leonard 4 and Charles 2) from Melbourne to New Zealand. The reason for such a move at this time is almost certainly due to economic conditions. Melbourne’s Land Boom of the 1880s burst spectacularly in the 1890s. Banks and other businesses failed in large numbers, thousands of shareholders lost their money and tens of thousands of workers were put out of work. While there are no reliable figures it has been estimated that Melbourne’s unemployment reached 20% in the 1890s. Things were looking better across the ditch!

By 1890 an export led economic recovery was taking hold in NZ. The election that year brought New Zealand’s first political party, the Liberals, to power. The Liberal era is synonymous with Richard John Seddon, Premier from 1893 until his death in 1906. The Liberals promoted themselves as the champion of the ‘ordinary New Zealander’. New Zealand now gained a reputation as ‘the social laboratory of the world’. In addition to women’s suffrage the Liberal government introduced a number of social welfare measures to protect New Zealand’s most vulnerable. The 1898 Old-Age Pensions Act offered a small means-tested pension to destitute older people ‘deemed to be of good character’. But Seddon’s image of ‘God’s own’ excluded ‘Chinese or other Asiatics’. He viewed the Chinese with considerable dislike, as did many in New Zealand’s mining communities.

The Liberal Government also wanted to encourage a steady workforce and sponsored the construction of a number of ‘Settlements’ – clusters of new houses built for rental by working class families under the ‘Workers’ Dwelling Act’ of 1905. The Dunedin Settlement was called ‘Windle’ and was located at Belleknowes. With this type of social policy surely there was a good future for a bricklayer in his mid 30s; a solid presbyterian and unionist who believed in god, hard work, family and community spirit? William, Emily and their family took the plunge and crossed the Tasman to resettle in Dunedin in about 1900-1902. Dunedin at that time was NZ’s largest city. William must have discussed the prospects of a joint venture in NZ with his brother, Albert Line Quennell. Albert was also a bricklayer, unmarried and 14 years younger than William. Albert left Melbourne and joined William and Emily in Dunedin about a year later. In May 1905 they each applied for and were granted an allotment in the Windle Settlement (Allotments 49 and 54), Rosebery St, Belleknowes.

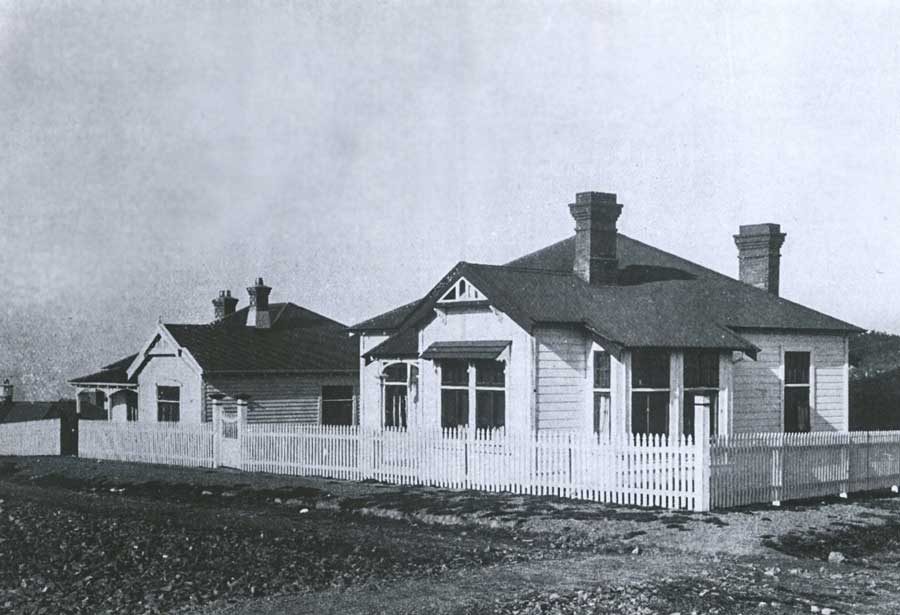

Windle Settlement Houses, Dunedin, 1907

So the subject of this story, young Wilfred Quennell, landed in Dunedin at about age 7 and completed his primary school ‘Education Board Examinations’ successfully in 1909. He participated in nearby Mornington institutions; the Church of Christ and the Rugby club. While playing for Mornington in an Association football match between the Tabernacle and Mornington Church of Christ teams in 1911 William broke his arm.

The injured limb was set at the Hospital, and Quennell then proceeded to his home. (Otago Daily Times, September 4th, 1911)

1911 was a big year for WIlfred as he also passed his Technical school examinations with first class honours in Mathematics and Chemistry in spite of having to cope with the broken arm. January 1915 proved even more eventful as he received news he had passed his Matriculation Examinations then 5 days later he enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) with the Otago Infantry Battalion (5th reinforcements). He was 21 years old and described on his enlistment form as 5 feet 7 inches, 11 stone, with a fair complexion, blue eyes and flaxen hair.

In June 1915, after some basic training at Trentham, his regiment set off on HMNZT ‘Maunganui’ bound for Egypt. As was often the case, a soldiers’ newspaper, the ‘Maunganui Mirror’, was produced onboard. Besides announcing that Kingsburgh had won the Melbourne Cup, it was full of lighthearted schoolboy humour reflecting the almost holiday mood on board:

The first day out was calm and bright, the sea and skies were blue

And everybody laughed and joked and ate their Irish Stew

But Lo! the morning following, Old Neptune had a frown

And half of us lay over the side as the ship rolled up and down.

In August Wilfred’s regiment was sent to Gallipoli. After only a week there he suffered a shrapnel head wound and was transferred to the hospital ship ‘Neuralia’ at Suvla Bay. He was treated on the ‘Neuralia’ for a few days and then transported to the ‘Luna Park’ section of the Australian 1st General Hospital at Heliopolis, Cairo. After about a month at Luna Park, Wilfred was declared unfit for service by a Military Board which noted his wound ‘had not yet healed’ and that he was ‘very irritable and nervous’. The Board repatriated him back to New Zealand aboard S.S. Tofua on 23rd September 1915 with a recommended 2 months sick leave. This leave was extended further when Wilfred was found to be suffering blepharitis and astigmatism.

On 25 November 1915, Wilfred attended a ‘Returned Soldiers Hearty Welcome At Mornington’;

Cordiality, admiration, and gratitude were the keynotes of an enthusiastic welcome tendered last evening by the residents of Mornington to about a dozen eons’ of the district who have returned from the front. The function was held in St. Mary’s Hall, which had been nicely decorated with flags and foliage, and there was a large and representative attendance of residents of the district. The Mayor of Mornington (Mr E. Sincock) carried out the duties of chairman in an efficient manner, and was supported on the platform by Mr J. J. Clark (Mayor of the city), the speaker for the evening, and several members of the local Borough Council. The appearance of the men was greeted with loud applause, which was prolonged for several minutes. The proceedings were opened with the hearty singing of the National Anthem, followed by a prayer of thanksgiving by the Rev. W. Greenslade. Mr Sincock then expressed his pleasure at seeing so many returned soldiers present to receive honour at the hands of the residents of Mornington, and he assured them they greatly appreciated their efforts. He had no need to dwell upon what had been accomplished by the men before them, but he would like to remind them that their boys were looked upon as occupying a front-rank place among the troops of the Empire – (Applause) From Mornington they had sent forward some 200 men and everyone of these had acquitted himself as they expected he would, and seemed to have made Nelson’s famous signal his motto. It was, however, with somewhat mixed feelings that reference was made to their boys, because they had to remember that some of them would never return, and of these it could truly be said that they bad fought the good fight and given their lives in a noble cause – the cause of honour and humanity.

The final address for the evening was delivered by Mr W. Davidson, whose remarks alternated between the serious and the humorous. He stated that the present great war was teaching our nation and the world at large many great and splendid and serious lessons, that were calculated to make.us realise that our chief duty lay in personal service. He felt that a new spirit would arise after the war, broadening men’s sympathies and making for unity and brotherhood and interdependence throughout the whole world. He felt that the kingdom of self-respect was coming over the universe, and that nations and individuals would learn to bow before its sway and to direct their lives in accordance with its influence, proceeding, the speaker struck a recruiting note and wound up with a story concerning a man who the other day remarked to an Irishman:

“I see that you are making jelly out of seaweed in Ireland, Pat” “Yes,” replied Pat, “and we are making mince-meat out of Germans, too.’ (Laughter)

Otago Daily Times, 25 Nov 1915

Then, a few days before Xmas, the local sports clubs that Wilfred had been involved in, provided their own tribute:

There was a good attendance of residents at St. Mary’s Hall, Mornington, last night to witness the ceremony of unveiling tho roll of honour established by tho Mornington Football and Cricket Clubs, as a tribute to their comrades who answered the call of Empire. Mr P. A. Shaw presided, and among those on the platform were Mr J. J. Clark (Mayor of Dunedin), Mr Sincock (Mayor of Mornington), Mr C. Payne, Captain Fleming, and the Rev. W. Greenslade. The proceedings opened with the singing of the National Anthem. The Rev. Mr Greenslade, before leading the assemblage in prayer, said that any man should count it an honour to take part in a function arranged for the purpose of honouring those men who were fighting our battles at Gallipoli. He was glad to know from the football and cricket clubs that in Mornington it could not be said truthfully that those who had learned to play the game on the football and cricket fields had not learned to play the game on the field of battle. – (Applause) It seemed to him that we had now come to the most critical period in connection with the war, but it was our duty to see it through. We were up against a wily and insidious foe, but he was satisfied that, with the assistance of the Most High, we must win through. – (Applause.)

The Chairman, in a few remarks, said that it was a coincidence that while they were thus engaged in honouring the men who had participated in the memorable landing at Gallipoli news had come through of the evacuation of Anzac and Suvla Bay by our troops. In these days of newspaper controversies, a good deal was said about blunders having been made on the peninsula – and there might have been, but so far as we were concerned Anzac would always be sacred to us – (Applause), because & good number of our comrades had fallen there. Not only would it be sacred for that reason, but because this was the first occasion that New Zealand had been able to show that, at the call of Empire, her sons had struck for righteousness and liberty in such a way as to cause wonder throughout the civilised world. – (Applause)

The Mornington Football and Cricket Clubs had sent a large number of men, and they felt that it was an honour to show their respect to their old comrades for the way they had responded to the call of Empire and risked their lives for the sake of their country in the hour of need.— (Applause.) These clubs had sent to the Mornington School and the High Street School photographs of the roll of honour, because, after all, most of the men who comprised these clubs came from these schools. It was their hope that the great work of these men would be indelibly imprinted upon the minds of the boys at school, so that, in after years, when they joined the clubs mentioned, those responsible for the institution of the roll of honour would be able, with safety, to hand to them this striking memento of brave men, with the assurance that it would be taken good care of. (Applause) Otago Daily Times, 22 December, 1915

On 10 February 1916, the Otago Daily Times reported that:

The members and friends of the Mornington Church of Christ were present in large numbers to bid au revoir to Sergeant W. B.Quennell and Mr R. Rogerson and Mr F. W. Grenfell. Sergeant Quennell was wounded at the Dardanelles, but has now recovered, and is once more leaving for active service.

In April 1916 Wilfred disembarked in Egypt for the second time. He was soon promoted to Sergeant and sent to Devonport, England on board the hospital ship ‘Nile’ in June 1916. He rejoined his Battalion at ‘Sling’ Camp. Sling was the New Zealand camp in Wiltshire where Kiwi reinforcements initially went prior to joining the front and where Kiwi casualties who were regaining fitness were sent.

The camp also housed some New Zealand conscientious objectors (among them Archibald Baxter and his brothers Alexander and John) who had been forced to join the army and sent all the way from New Zealand to England to make an example of them. After the end of the war, there were 4600 New Zealand troops stationed at the camp and the camp became a repatriation centre. At that time there was unrest in other camps as a result of delays in demobilising troops. To try to restore order the “spit and polish” regime was enforced and route marches ordered. The men requested a relaxation of discipline as the war was over and they were far from home, however this was refused and the troops rioted, stealing food from the mess and all of the alcohol from the officers mess. In an attempt to resolve the situation, the officers and men were promised no repercussions, but this promise was not honoured; and somewhat ironically the ringleaders were arrested, jailed and immediately shipped back to New Zealand. To occupy them, the New Zealand soldiers were put to work carving the shape of a large Kiwi in the chalk of the hill that overlooks the camp. The Bulford Kiwi as it is known is still there today. (Wikipedia)

In March 1917 Wilfred was transferred to Codford camp and posted with the 3rd Otago Battalion, 4th Infantry brigade where he apparently assisted with troop training:

Mr W. B. Quennell, of Embo street Caversham, informs us that his son, Wilfred Bruce Quennell, whose name appears in the ballot, left with the Fifth Reinforcements and was wounded on Gallipoli and invalided home. Having recovered, he returned with the Tenth Reinforcements and on arrival at Sling Camp was employed on the instructional staff as a sergeant-major, in which capacity he has been serving since – a period of about 11 months. (Otago Daily Times, 9 May 1917)

Wilfred returned from a period of leave and was posted to the 2nd New Zealand Entrenching Battalion on 8 April 1918.

The activities of the Entrenching Battalions were directed to the construction of rear defences, road formation and repair, tunnelling, cable-laying, etc. Some of this work was of a very heavy nature; but throughout the whole course of operations, and whatever the conditions, the Entrenching Battalions established a high and lasting reputation for their great working ability.

Towards the close of January, 1918, the receiving centre for all New Zealand reinforcement troops arriving in France, originally and up to that date established at Etaples, had been transferred to Abeele, west of and in the area of Ypres, where it was commanded as formerly by Lieut.-Colonel G. Mitchell, Otago Regiment. When the German offensive was launched in March, 1918, the Entrenching Battalions were employed in the back areas of the Ypres Salient. On April 11th, two days after the German attack in the northern zone was launched, the 2nd Entrenching Battalion received warning orders to hold itself in readiness to move. At 5 p.m. on April 12th the formation, commanded by Captain (Temp.-Major) J. F. Tonkin, moved out of camp prepared for action, and headed for Meteren, with orders to report to the 33rd Division. The journey to Meteren encountered the extraordinary traffic which the tide of a rear-guard battle promotes and swells – the hurried forward march of supporting troops, the columns of motor-lorries and ambulances, the passage of artillery and transport, and, unforgettable above all else, the stream of civilian refugees fleeing from the threatened destruction. Passing through and beyond all this extraordinary movement, the 2nd Entrenching Battalion arrived at the outskirts of Meteren. Orders were received to dig in behind the village, but it was not long before the several platoons of the Battalion were drawn upon to reinforce the defensive line taken up by English troops about Meteren.

On April 15th the enemy attacked and enveloped the town of Bailleul. At daybreak on the 16th the sweep was continued in strength against Meteren. The 2nd Entrenching Battalion at once became heavily involved.

There were wide intervals of distance between the several posts which constituted the general line. For that reason mutual support was somewhat difficult. But the whole situation on the left was soon to be seriously complicated and imperilled by a set of circumstances over which the Otago troops had no control. With the fall of Bailleul and the anticipated continuation of the enemy’s advance towards Meteren, it was notified that the English troops still further to the left would probably retire down the valley. In that case the New Zealand troops on the left of Meteren were to conform by withdrawing to the newly constructed switch trench in rear of the village. The withdrawal by the English troops did eventuate during the night; but they failed to advise the adjoining posts of their action. Before daybreak on the 16th the garrisons of our advanced positions were notified by their own Headquarters that it was expected that the enemy would attack, in which case a withdrawal was to be effected, while at the same time endeavouring to check the hostile advance.

The German attack, preceded by heavy machine gun fire, developed about daybreak. The enemy, meeting no resistance on the left, immediately exploited his initial success. It was not long before our positions were under fire practically from three sides. The opportunity for effecting a withdrawal had now passed. The platoon of the 1st Company of Otago, commanded by Sergt. T. Sounness, endeavoured to get clear by forcing its way along the Bailleul-Caestre Road, but failed. The two platoons of the 2nd Company, now heavily pressed by the enemy, their ammunition practically expended, and all avenues of escape closed, decided that in the circumstances their only alternative was to comply with the demand for surrender. Thus three platoons, or a total of 210 other ranks, fell to the enemy as prisoners. Only two men had succeeded in getting through, one a lance-corporal who was despatched by Sergt. Sounness with a message indicating the position and asking for assistance, and the other a private of the 2nd Company.

This was the single instance in the whole of the campaign where any considerable numbers of New Zealanders were taken prisoners. (New Zealand Electronic Text Collection)

Wilfred Bruce Quennell was one of the New Zealand troops taken prisoner at Meteren on 16 April.

Had timely warning been received of the withdrawal of the supporting English troops, this loss must have been averted. Even had the general line been maintained at its original strength, it could have offered an appreciable resistance to the enemy, or at least have withheld his advance sufficiently to permit of an orderly withdrawal. On the other hand, it must be admitted that a large number of the troops concerned in this unfortunate affair were entirely new to action; the formation suffered from a shortage of experienced leaders, and ammunition supply had in many instances been seriously reduced on the journey from Abeele to Meteren because of an impression that the Battalion was going to construct trenches, not occupy them. But even allowing for these considerations, it is doubtful if experienced and better prepared troops would have fared differently in the same situation. The disaster might have been delayed, though not wholly averted.

The majority of those who had the grave misfortune to become prisoners of war in the Meteren operations were for some time subjected to the cruellest and most inhuman treatment. For a definite period they were confined in the “Black Hole of Lille,” an underground chamber of the fort on the outskirts of Lille town, where the conditions of confinement were indescribably bad. It was sufficiently clear that this was a deliberate and calculated form of German torture, intended to break the spirit of prisoners before sending them out to work in gangs. (New Zealand Electronic Text Collection)

The prisoners were marched to Steenwerck, about 9 Kms away and then a similar distance to Estaires. This was the town the Germans had taken only a few days earlier. Their eventual destination was the infamous Fort McDonald on the outskirts of Lille. This place was described as the “black hole of Lille” and had “dungeons”. Prisoners were not well treated. It was said that the Germans used this camp to “soften up” the prisoners before sending them to work. (http://nzwargraves.org.nz/)

“Fort McDonald was practically underground, well built and with a touch of French beauty on the court yard walls: but the hideous German eagle – the hungriest looking creature ever pictured – was nailed upon the wall, while on the opposite side was a sign in German:

God Give the Kaiser a grip of the land,

Then will we Germans stay our hand!

We were marched into underground rooms. The number 104 was printed on our door and 104 men were put in it. When lying down close together we just filled it. There was a cement floor, no bedding, no straw, no food and no fire. We were not allowed out of the room on any account. A half barrel in the room did duty as ‘closet’ and when it was full some sentries took four of the prisoners who, with a bucket, ladled ‘it’ out into filthy buckets which they carried out. We were supplied with a liquid made of a few cabbage leaves and water; but we were not supplied with any tin or basin to take it in; so that anyone who had no helmet had to wait for a mate’s. We also received half an ordinary slice of black bread per day. I won’t attempt to describe the atmosphere in the room”. (An Australian soldier’s description of the ‘black hole of Lille’)

In a letter to his uncle (George Bowen Quennell) who was living in London at the time dated 5 days after his capture, Wilfred states that he is “quite well”.

During a 1919 medical examination after the war the doctor noted that Wilfred had chest pains and that he stated they were like what he experienced as a prisoner of war when he was coughing up sputum streaked with blood. He revealed that he had been taken to a hospital in Stargard (Poland) so presumably he didn’t spend too long in the ‘black hole’ at Lille. There are 2 photographs of Wilfred as a PoW; both picture him in the French town of Perenchies with other prisoners of war. Perenchies is only about 10 kilometres from Lille in the north of France and I presume that these PoWs were put to work by their German guards.

After about 8 months as a PoW, Sergeant Wilfred Quennell was released and eventually arrived at the Ripon camp in Yorkshire on 14 December 1918. The Ripon camp had been transformed to specialise in receiving repatriated Allied prisoners of war returning to England via the port of Hull. These soldiers were fed, cleaned, paid and were then required to make statements about their PoW experience before being given 2 months furlough.

Wilfred embarked at Liverpool for New Zealand onboard ‘Somerset’ on 2 July 1919. In 1924 he married Jeannie Barr Sandilands and they had 4 children: Marjorie, Ngaire, Stanley and Lindsay.

Wilfred developed his skills as a bricklayer (like his father and grandfather before him) after the war and created his own building business in Dunedin, which he named ‘W.B.Quennell & Sons’. He also served in the National Army Reserve in World War 2 as a private from 29 July 1940 to 4 August 1942 when he was sent to repair chimneys demolished in the big earthquake centred on Masterton.

Until about 1954 he continued working in his own business, then as his health began to deteriorate Wilfred became semi-retired and worked as a clerk for Cadbury Fry Hudson until several months before his death. He died at home in Dunedin from emphysema in 1964.