A Lean Glean of Lysergic Acid Diethylamine

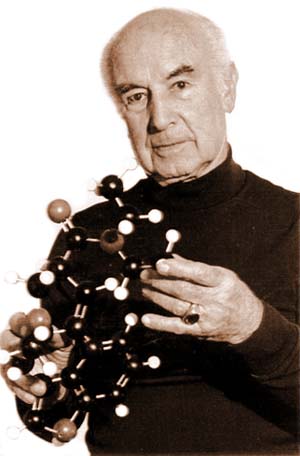

While working as a psychiatric nurse on night duty at a large mental hospital in the late 1970s, I found an old, large, leather bound volume which contained dozens of records of the administration of Lysergic acid diethylamine (LSD) to patients with psychotic illnesses in the 1960s. I remember being amazed that such an unpredictable and then socially forbidden ‘psychedelic’ substance had been used experimentally on people with diagnosed psychoses. I didn’t know at the time that this was relatively common in mental hospitals across the world at that time. LSD was first synthesised in 1938 by Dr Albert Hoffman.

While re-visiting LSD in 1943, he accidentally touched his hand to his mouth, nose or possibly eye, ingesting a small amount and discovered its powerful effects. It came to be widely used by the counter-culture of the 1960s and, although there were fearful reports of frequent adverse reactions and dangers, but there was always interest in its potential as a medically therapeutic agent.

While re-visiting LSD in 1943, he accidentally touched his hand to his mouth, nose or possibly eye, ingesting a small amount and discovered its powerful effects. It came to be widely used by the counter-culture of the 1960s and, although there were fearful reports of frequent adverse reactions and dangers, but there was always interest in its potential as a medically therapeutic agent.

Drug Digs Back Into Childhood

A new drug discovered by a Swiss enables a person to relive early childhood experiences even back to the age of two years. It has been used in 60 cases at Powick Mental Hospital, near Worcester, England. The drug is called lysergic acid diethylamine. Given the drug, a patient remains conscious but becomes a child again, reliving with complete reality forgotten events. When the effect passes, the patient still remember details of his past. These often include deep-seated causes of a mental disorder. Sometimes this discovery is enough to cure. Otherwise it enables doctors to continue effective treatment.

Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners’ Advocate (NSW : 1876 – 1954), Mon. 7 June 1954

Death risk in ‘kitchen’ LSD

SYDNEY, Sunday

Hundreds of young people are risking their sanity and their lives from home-made LSD, police have warned. The formula for the drug has been circulating for weeks among teenagers in Sydney. Although the formula is difficult to follow in its pharmaceutical terms, many producers of the drug are believed to be using a step-by-step recipe for laymen. All ingredients except lysergic acid are readily available in Sydney.

Authorities say the use of other forms of ingredients to counter the difficulty in obtaining the acid is likely to produce an impure drug capable of causing lunacy and death.

Teenage mental patients

Drug Squad police have warned would-be producers of the drug to abandon their attempts. State health authorities are believed to be concerned at the growing number of teenagers admitted to mental hospitals after taking LSD and suffering prolonged adverse reactions.

Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 – 1995), Monday 16 October 1967

LSD AND THE FACTS

The Students’ Representative Council of the Australian National University decided this week to seek Government publicity of the dangers of the hallucinogenic drug lysergic acid diethylamide, better known as LSD. The council’s concern is proper and its decision sensible and responsible. Rumour and ignorance are a poor guide for young people drawn to experiment with LSD. The risks so far apparent suggest that the Government is well justified in legislating a maximum two-year prison sentence, a $52,000 fine or both for illegally dealing in or even possessing this chemical, but that is not the end of the matter. The threat of heavy penalties alone is unlikely to deter many young people from taking risks, though it may help to keep down trafficking. The best weapon may be knowledge. What is required is nothing less than an exhaustive study of the drug (and possibly of some others), perhaps published as a Government White Paper.

Australians have good excuse to be confused by this new issue, as are Americans who have lived with it far longer than we. On the one hand there is the strong disapproval of LSD by constituted authority – tantamount for some young people almost to a recommendation. On the other is the testimonial of such disparate persons as the late Aldous Huxley (who look not LSD but similar mind bending preparations), actor Cary Grant and “beat” poet Allen Ginsberg. The Beatles have confessed to taking LSD; a song of their most recent album has been interpreted by others as the description of a “trip” under its influence. With such examples, what should the young think? LSD is allegedly non-addictive, which makes the opportunity to take a little soaked into blotting paper or a lump of sugar appear far safer than, for instance, taking a first dose of heroin.

Mental disturbance

Yet it is admitted that the person taking a trip is not fully in control of his or her self. And it is in this fact that the most obvious danger appears to lie. In a murder trial now under way in New York a man is alleged to have killed a woman while he was “flying” on LSD. Death by LSD accident is on record. When a window looks like something else, what is to prevent one stepping through on to a street several stories below? There is a risk, too, of serious mental disturbance from a bad trip, causing hysterics or depression. And an overdose may well be lethal; one ounce of the pure drug is sufficient for 284,000 trips. If the scientific inquirers who killed an elephant in an Oklahoma zoo with an overdose can miscalculate, so can the lay member of the public, or the source which provides his supply of LSD. Recently, and most importantly, there have been reports that the drug can damage the chromosomes and affect future children, though it may be that this danger results from repeated use rather than the casual experiment. The reports should at least be a warning to those who put up the specious but shallow argument that the dangers of USD are analgous to the obvious and well-known dangers in misusing alcohol. Again, there is the fear that experiments with LSD will lead some users on to seek experience in the dangerous addictive drugs.

In the present confused state of public knowledge there is a fair chance that the heady recommendations of the hippies and other users will continue to influence the small but probably growing section of the community interested in taking LSD. A properly documented account of the drug and its dangers, as suggested by the ANU students, would not cause all these people to shy away from it, but might well influence some to do so.

Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 – 1995), Thursday 28 September 1967

Fast forward 24 years and the strong interest in LSD as a therapeutic agent continued. It was also used secretly and cruelly by the CIA!

Scientists still believe LSD is a key to unlocking the brain’s secrets

By LEE SIEGEL

It may seem like a flashback trip to the psychedelic Sixties, but scientists still study the drug LSD to scrutinise the brain, mental illness, sensations and emotions.

LSD and other hallucinogens are very powerful tools in helping us answer a very old-and important question: What is man, Why are we here, and who are we? said David Nichols, a professor of medicinal chemistry at Purdue University in Indiana.

By altering and amplifying perceptions and feelings, LSD can help us understand the structure of the brain and personality, How we process sensory information — why things look, smell and sound the way they do — and what emotions are, how we feel love, how we feel hate, he said.

Yet only a few United States scientists study LSD and they all conduct laboratory or animal research. Authorised experiments on humans have not been conducted for years there.

Some LSD advocates blame government restrictions for preventing the drug from being used in psychotherapy or human experiments, which can be conducted only by medical doctors.

Others say the Government allows studies on humans, but scientific interest and government funding dwindled when the drug faded as a social problem. They predict LSD experiments on people will resume once legitimate scientists are ready.

LSD – lysergic acid diethylamide was first synthesised in 1943. Also known as “acid”, its ability to produce vivid hallucinations, known as a “trip”, was discovered that year when Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman ingested a tiny amount.

The Central Intelligence Agency, fearing that the Soviets and Chinese would use LSD to brainwash American diplomats, began financing research in 1953 as part of Project MK-ULTRA. LSD was given to unwitting subjects, resulting in at least one suicide and the CIA’s 1988 agreement to pay a $US750,000 settlement to the people who were subjected to experiments.

During the 1960s, LSD became the tool of a social and political movement dedicated to freedom, creativity, self-discovery and opposition to the Vietnam War.

LSD was used by some psychotherapists to dredge up patients’ innermost thoughts. Many young people took LSD to expand consciousness and see reality in an unfamiliar and astonishing light.

But some people “freaked out” as LSD caused panic or activated latent mental illnesses. Others were haunted by “flash backs”, sudden recurrences of hallucinations. A few thought they could fly, and jumped to their deaths.

The popularity of the drug in the 1960s spurred research and laws making its use illegal. The US Drug Enforcement Administration lists LSD as a “schedule 1” drug, which means it has high potential for abuse, no currently accepted use in medical treatment and a lack of safety when used even under medical supervision.

National Institute on Drug Abuse surveys indicate illicit use of LSD has remained relatively constant. Almost two percent of US high-school seniors are users and 8.7 per cent have taken LSD at least once.

With few people experiencing “bad trips”, scientists show less interest in LSD than they did during the 1960s.

About 160 studies a year dealt with LSD from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. To day, only one-fourth as many journal articles mention the drug. In the last two years, however, only about 10 scientists were given LSD by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which dispenses illicit drugs for research, said drug-supply coordinator Robert Walsh.

But LSD research still holds promise because

if you understand how psychedelic drugs cause peculiar mental changes, then you’ll understand how the brain normally regulates features like perception and emotion, said Dr Solomon Snyder, director of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University.

LSD resembles serotonin, a natural chemical that helps transmit nerve impulses among brain cells. Serotonin is important in sleep, appetite, perception and in certain mental disorders such as depression, mania, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder, said Dr Barry Jacobs, director of neuroscience at Princeton University.

Scientists have learned LSD and serotonin act on the same brain cell components, called receptors. So LSD studies can help scientists understand serotonin’s role in normal brain chemistry and in mental illness, said Daniel X. Freedman, a psychiatrist – pharmacologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

If researchers can learn how LSD distorts reality,

we might have insight into why people with schizophrenia have hallucinations, said Dr Floyd Bloom, neuropharmacology chairman at the Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation.

People who take LSD repeatedly over the course of a few days quickly develop tolerance, which means the drug no longer produces hallucinations. Freedman studies how rats develop tolerance to LSD, research aimed at developing medicines to halt hallucinations in certain mental patients.

In the 1960s, some psychotherapists tried LSD for treatment of alcoholism and psychiatric problems, but the few careful scientific studies showed no specific advantage of LSD as a treatment for any thing, Freedman said.

The Government would not allow even experimental use of LSD for treatment unless other drugs had been tried and failed, DEA spokesman Bill Ruzzamenti said. Critics said that effectively banned LSD for psychotherapy. .

Here, the case for reforming the UN ban on the use of hallucinogenics for medical research….

Here, the case for reforming the UN ban on the use of hallucinogenics for medical research….

Psychedelics, used responsibly and with proper caution, would be for psychiatry what the microscope is for biology or the telescope is for astronomy. These tools make it possible to study important processes that under normal circumstances are not available for direct observation. Stanislav Grof (1975)

Use of hallucinogens has survived to the present day in indigenous cultures and some churches, such as the Santo Daime church in Brazil (and now beyond) that uses ayahuasca in its church ceremonies, even in children. The use of ibogaine for self- enlightenment in West Africa has now developed worldwide and has become popular as an aid to overcoming addiction. Psilocybin as ‘magic mushrooms’ have been used in many cultures across much of the world, and are still taken by many young people in the UK despite attempts to ban them by making their possession illegal. The reasons for – and benefits of – this widespread social use of hallucinogens throughout human society is an important question for social psychology.

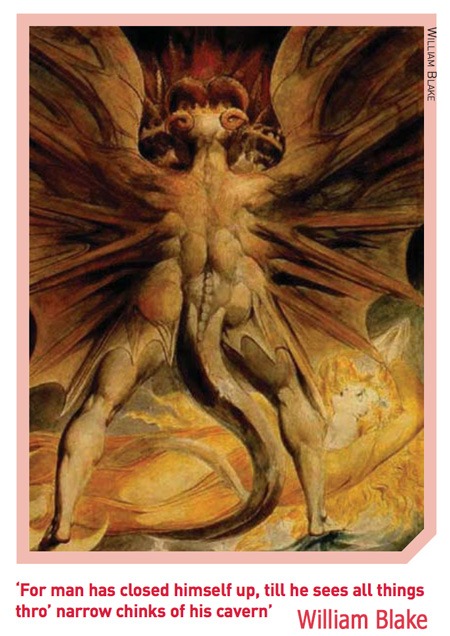

In contrast, ‘Western’ society has promoted other drugs, particularly alcohol, for social engagement, worship and pleasure. When hallucinogens, particularly the new longer-acting synthetic one LSD, began to enter popular culture in the early 1960s (the ‘flower- power’ movement) it was seen as a major threat to the current political order and so LSD plus all other hallucinogenic chemicals such as psilocybin and dimethyltryptamine (DMT) were rapidly banned in the USA and then under the UN drug conventions.

To me – and I speak here as a former Chair of the UK government’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs – the justification for the banning was a concoction of lies about their health impacts coupled with a denial of their potential as research tools and treatments. Indeed their banning demonstrates the chilling power of drug regulators and enforcers to control the drug agenda, for the ban was enacted in the face of opposition from leading and open-minded politicians such as Bobby Kennedy (whose wife Ethel had undergone or was undergoing LSD therapy at the time at Hollywood Hospital). The discussion between him and them shows the challenge of getting to the truth.

Why if [clinical LSD projects] were worthwhile six months ago, why aren’t they worthwhile now? … We keep going around and around… If I could get a flat answer about that I would be happy. Is there a misunderstanding about my question? I think perhaps we have lost sight of the fact that LSD can be very, very helpful in our society if used properly.

(Kennedy, quoted in Lee & Shlain, 1985, p.93)

As is the case with almost all international drug-related legislation, the UK government slavishly followed the US lead and psychedelics were banned here in 1964. The reason for this strict control is to prevent the recreational use of these drugs, particularly by young people. The controls are supposedly designed to reduce their harms, although in the case of hallucinogens these harms are clearly less than those from most other drugs, including legal ones such as alcohol (Nutt et al., 2010). This decision has efficiently stopped research into these drugs to the detriment of researchers; worse still, many thousands of patients have been denied potential new medicines.

Almost all nations in the world are signatories to the UN conventions, so the ban on use is almost totally worldwide, with the only exceptions being made for plants growing wild which contain psychotropic substances from among those in Schedule I and which are traditionally used by certain small, clearly determined groups in magical or religious rites (1971 Convention Commentary Article 32:4).

Before these UN regulations were brought in, LSD had been widely studied with about 1000 studies involving 40,000 subjects (Masters & Houston, 1971). The pharmaceutical company that invented LSD, Sandoz, saw its huge potential for understanding the brain and as a possible avenue to new treatments, so they made it widely available to the worldwide scientific community. In the 50 years since its ban, there has been almost no new research despite remarkable advances in neuroscience technologies such as PET and fMRI that could allow a much greater understanding of its actions than were possible in the 1950s. The limited research now developing in this field has already revealed remarkable and unexpected insights into how these drugs produce hallucinations (see Carhart-Harris et al., in this issue). They also offer a possible new human model of psychosis against which to test new antipsychotic agents.

Before these UN regulations were brought in, LSD had been widely studied with about 1000 studies involving 40,000 subjects (Masters & Houston, 1971). The pharmaceutical company that invented LSD, Sandoz, saw its huge potential for understanding the brain and as a possible avenue to new treatments, so they made it widely available to the worldwide scientific community. In the 50 years since its ban, there has been almost no new research despite remarkable advances in neuroscience technologies such as PET and fMRI that could allow a much greater understanding of its actions than were possible in the 1950s. The limited research now developing in this field has already revealed remarkable and unexpected insights into how these drugs produce hallucinations (see Carhart-Harris et al., in this issue). They also offer a possible new human model of psychosis against which to test new antipsychotic agents.

The clinical potential of hallucinogens was always seen as one of the most important advances. The founder of Alcoholics Anonymous reportedly became abstinent after an LSD experience in which he saw he could escape from the control alcohol had over him, and many others tried the same approach. A recent meta-analysis of the old clinical trials in which LSD was used to treat alcoholism (Krebs & Johansen, 2012) found that the effect size of LSD was as great as that of any other treatment for alcoholism developed since. This apparent clinical utility of LSD has been denied to millions of patients, and alcoholism is now the leading cause of disability for men in Europe (Wittchen et al., 2011).

Another of the original benefits of LSD, as a way to come to terms with dying, could offer a more humane and positive alternative to sedatives and opioids. The value of this approach has just resurfaced with the first LSD study in 50 years (Gasser et al., 2014) where it again was shown to reduce anxiety in those with terminal illness. This complements the approach of Charles Grob in this issue, using psilocybin for cancer anxiety.

Other Schedule 1 psychedelic drugs have similar potential for treatment uses. Ibogaine is licensed for the treatment of addiction in New Zealand. Psilocybin, obtained from ‘magic mushrooms’, is a shorter-acting version of LSD that has been shown to be a possible treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (Moreno et al., 2006) and cluster headaches (Sewell et al., 2006). Roland Griffiths’ group in Johns Hopkins has shown that psilocybin given in a psychotherapy setting can produce very long-lived and profound improvements in mood and well-being (Griffiths et al., 2008).

That this small handful of studies represents all the clinical work in the

last 50 years proves how destructive the banning of hallucinogens has been on treatment research.

(David Nutt is Professor of Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London)

Excerpt from “A Brave New World For Psychology”, David Nutt, Psychology Magazine, Vol. 27, No.9, September 2014

http://issuu.com/thepsychologist/docs/psy09_14web/84?e=1106616/9079836

(Note: The Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 is a United Nations treaty designed to control psychoactive drugs such as amphetamine-type stimulants, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and psychedelics signed in Vienna, Austria on 21 February 1971).

Albert Hofmann, who discovered LSD in 1943 and used it in small doses throughout his life, said on his 100th birthday in 2006…

In ordinary perception, the senses send an overwhelming flood of information to the brain, which the brain then filters down to a trickle it can manage for the purpose of survival in a highly competitive world. Man has become so rational, so utilitarian, the trickle becomes most pale and thin. It is efficient, for mere survival, but it screens out the most wondrous parts of man’s potential experience without his even knowing it. We’re shut off from our own world. Primitive man once experienced the rich and sparkling flood of the senses fully. Children experience it for a few months until “normal” training, conditioning, close the doors on this other world, usually for good. Somehow, the drugs opened these ancient doors. And through them modern man may at last go, and rediscover his divine birthright.