Alfred Sydney Quennell was born on 25 February 1891 in Balwyn, Victoria. He was the thirteenth, and perhaps unlucky last, child of William Thomas and Mary Quennell (their story can be read HERE). This photo is one of only 2 images I have of Alf. He is a fine looking, healthy young man about 11 years old posing with his whole family. As a young boy I have a vague memory of visiting him at his home in Hampton with my mum. He was terminally ill at the time with respiratory complications from the gassing he was subjected to in France during world war 1. Alf was a 23 year old soft-goods salesman who still lived with his family at 7 Weinberg Grove in Hawthorn when he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) on 20 February 1915. He was 5′ 6 5/8″, had brown eyes and fair hair and weighed 11 stone 4 pounds. Each person enlisting in 1915 signed an oath which includes:

I swear that I will well and truly serve our Sovereign Lord the King in the Australian Imperial Force until the end of the War (and a further period of four months thereafter) …and that I will resist His Majesty’s enemies and cause His Majesty’s peace to be kept and maintained ….SO HELP ME GOD.

‘Sovereign Lord’ King George V indeed had a number of enemies which needed resisting after he declared war on Germany 6 months earlier based on an English treaty protecting Belgium’s neutrality.

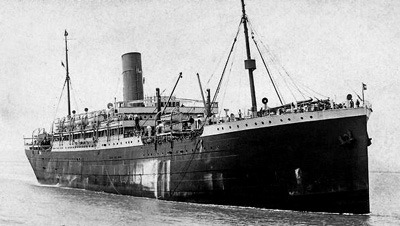

Alfred had joined the 6th infantry brigade of the 23rd Battalion and after some initial training at Broadmeadows they embarked from Melbourne, bound for Egypt, on the troopship HMAT Euripides on 8 May 1915.

The collected letters and diaries of fellow 23rd battalion soldiers provide many insights into what army life was like for our Alfred, especially the letters of ‘Goldy’ Raws which are often quoted in this account.

You will know that the King’s regulations lay down that no officer shall shave his upper lip and practically all the officers have started on this strange adventure. Mine is very fierce looking and will stick out straight. It is, however, deemed satisfactory. I still continue to get on with my men and I grow to like them as I know them better. These men in my platoon, you will understand, are completely under my control…

By 30 May, 3 weeks out to sea and 5 soldiers had died in the past 6 days; 1 of sunstroke and 4 others of pneumonia. Several others lay in the ship’s hospital – given ‘little hope’ by the doctors. As they approached the tropics the doctors warned everyone onboard to wear their ‘cholera belts’. These were supposed to suppress perspiration and prevent abdominal chills and therefore enteritis – there was no medical evidence supporting their use but they continued as a strange anachronism of the British Army which the Aussies copied.

By June 11, the Euripides had sailed through the Red Sea and Suez canal and reached Alexandria. As they waited to disembark and leave for Cairo, the soldiers were regaled with stories of the ‘front’ from 4 wounded officers. The officers told them that ‘the Australians have done well, but they have lost terribly’. Nothing would delight them more than if the war could be over so that they had not to go back to fight. They didn’t mind the bullets whizzing about, ‘it is the shells that are so terrible’. Soon after, the 6th brigade was at their base in Heliopolis, about 3 miles from Cairo. The daily routine consisted of Revielle at 4am, Parade from 5-8am, a lecture in the large tent from 10.30am-12 and more Parade from 4.30-7.30pm.

If I do not reply to your letters it is because I have not received them. There are 25 tons of mail undelivered at Cairo. It is as hot as the place we hope none of us will go to.

After a a couple of months in Egypt the 23rd battalion was called up to Gallipoli following heavy losses incurred by the ANZACS in the failed ‘August Offensive’. The Brigadier of Alfred’s brigade, Colonel Linton, was drowned when the ‘Southland’, one of the troopships transporting them to Gallipoli was torpedoed in the Aegean sea. Alfred’s brigade landed at Gallipoli about 10pm on September 4th ...’a very quiet landing with practically no casualties’. They spent 2 days at the beach then moved up to the firing line trenches. By 13th September, at ‘Lone Pine’, Goldy Raws, one of Alfred’s brigade, wrote…

I am sitting in a trench about 8 yards behind our firing line – the enemy’s trenches are 40 yards from where I sit. In many cases along the line we hold, the trenches are much nearer and in some places only 6 yards intervene. The smell of ‘dead Turk’ which I will not describe to you, is not as bad as you might imagine …except when the Turks are bombing and the dead bodies round about get stirred up a treat.

The section of trench they were holding was one of the most difficult positions along the whole line and meant that they had 48 hours in the trenches and then were relieved for 48 hours – usually alternating with the 24th Battalion.

Bombs were able to be thrown by hand fully well anywhere here on to our parapets, if not into the trenches, and frequent artillery fire to which our position is open, there is a strain about it and the 48 hours off is a God-send. …we can all feel again what a horrible thing this war is and you who are growing up and all young people of little or great influence must at the completion of this war see what can be done, not by Peace Societies, but by the society of the world, of human hearts and human brains must work to see what means can be used to make a repetition of this thing impossible.

On 29th November, Alfred was wounded ‘in the side’ and admitted to the 2nd L.H. Field Ambulance but discharged back to his Unit on the same day. Australia’s official War Historian, Charles Bean recorded the following lines in his diary in relation to the day Alfred was wounded:

Freezing hard last night and most of this day and again tonight. Two guns on chessboard were firing down at ammunition dump hospital but without luck. Sent 2 or 3 shells into hospital, one into latrine, where 5 men were sitting on; it spattered them and did no harm. A man was blown thro’ a ventilator in hospital roof the other day – shell burst below him when he was sitting on a stool and he was unharmed and on duty next day. Hospital today moved patients into saps – stretcher cases lying down along one part, walking cases standing in another. One shell landed in sap and broke legs of a standing up case.

Surely not …a ‘spattered’ Uncle Alf? The battalion left Gallipoli on 19th December. Of the 960 who landed there, 250 were killed or wounded and 350 were taken sick. In the last 3 weeks 70,000 troops were withdrawn and in the last 2 nights 12,000 left apparently without the Turks suspecting the evacuation.

After weeks of recuperation and an outbreak of mumps, the 6th Brigade was ‘inspected’ by General Birdwood and the Princes of Wales on March 21st, 1916 – just prior to their deployment to the battlefields of France.

The Prince looked very slight. He rode a beautiful horse but he rode very short and lifted very high. He did not look to me more than seventeen but he is, you know, twenty one.

Alfred’s brigade embarked on the ‘Lake Michigan’ and sailed to Marseilles, France, disembarking on March 26th, 1916. The 660+ soldiers immediately boarded a troop train bound for the ‘Western Front’, near Armentieres in the north of France.

On April 1, the brigade was given its first lecture about gas attacks, along with instructions in the use of ‘gas helmets’. A week later each soldier was issued with 2 gas helmets. The battalion, whose strength had swelled to about 950 soldiers and 29 officers, then marched the 6 or so miles to Fleur-Baix and occupied trenches there on April 11. It was bitterly cold and it rained for days – there was a foot of water over the trench duckboards in places. On April 27th the battalion received its first ‘gas alarm’.

Our artillery opened up from all along the line behind us …gas-gongs, special bugles, were sounding everywhere and with the thunder of our guns one could scarcely hear oneself speak. The object of artillery firing was to fire shrapnel right into the gas and thus endeavour to dispel it …the gas did not come down as far as us. It was confined to a section of some 800 yards and was a mile away from us. It is deadly stuff and our troops in the section on which it came suffered heavily.

Nursing staff at field hospitals reported that gas attacks were particularly prevalent about this time in 1917:

Mustard oil shells are being used by the enemy, in consequence of which we receive many patients with burns therefrom, the eyes specially being much inflamed. At times, large blisters form on the body.

Mustard gas is not a particularly effective killing agent (though in high enough doses it is fatal) but can be used to harass and disable the enemy and pollute the battlefield. Delivered in artillery shells, mustard gas was heavier than air, and it settled to the ground as an oily liquid resembling sherry. Once in the soil, mustard gas remained active for several days, weeks, or even months, depending on the weather conditions.

Early in May when the battalion was ‘in reserve’ (out of the trenches) and recuperating they were given 4 days training in bayonet fighting by officers who had just returned from ‘Brigade Bayonet Fighting School’. On June 1st half the battalion went to Croix du Banc for an inspection and address from Australian Prime Minister, Billy Hughes.

On 29th June Alfred was wounded while participating in a carefully planned night time raid on the German trenches. The action is detailed in Operation Order No.11 and labelled the ‘6th Brigade Stunt’ in the brigade’s war diary.

Raid. At midnight a raiding party of 252, drawn from 21st /22nd /23rd battalions carried out a successful enterprise on enemy trenches. The line was entered in three places. The 23rd battalion party commanded by Capt. H.M. Conran, Lieut. W.A.Cull (Scout Officer) entered at I 26 B 10 61/4 (Ref. Map 36 N.W. 1/10,000) considerable difficulty in entering as wire had not been cut. Party remained in enemy trench 8 minutes doing considerable damage. Our artillery & French Mortars co-operated. The results of the raid by all parties were. Enemy: Killed 80. Prisoners 5. 23rd Battalion casualties were O.R. 1 Killed. 4 wounded. 1 missing. (23rd Battalion, 6th Infantry Brigade War Diary, Vol. XIV, Page 9)

Fleur-Baix. The 6th brigade; just arrived in Flanders from Egypt. The men are balancing their newly issued steel helmets on the ends of their rifles.

There is no indication in Alfred’s military record that he was transferred out of his unit at this time for any medical treatment, so I presume his wounds weren’t too serious. However one of the brigade’s Colonels was evacuated suffering a ‘nervous breakdown’. In July the battalion was ordered to march to Wizernes from where it ‘entrained’ via Callais then down to the town of Ailly-sur-Somme. After further training and marching they finally arrived in the town of Pozières and took up reserve trenches there on 26th July. Pozières is situated at the centre of what was the Somme battlefield. The Battle of Pozières and Moquet Farm are infamous in Australian military lore for the 23,000 casualties, including 6,800 deaths, incurred in about 6 weeks. This was greater than the total casualties and deaths suffered in the whole Gallipoli campaign. In the words of our official war historian, Charles Bean;

the Pozières ridge “is more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on earth”

Lieut. ‘Goldy’ Raws, whose diary I have quoted extensively here, was killed on July 29th at Pozières. His brother, Alec, was also fighting at Pozières. A week later, still hopeful his brother was ‘missing’ or taken prisoner, rather than dead, Alec wrote in a letter home…

The first night I went right up to the front line, our battalion, or nearly all of it, had to march for 3 miles, under shell fire, go out into No Man’s Land in front of the German trenches and dig a narrow trench …I went up from the rear and found that we had been cut off, about half of us from the rest of the battalion and were lost. I would gladly have shot myself, for I had not the slightest idea where our lines or the enemy’s were and the shells were coming at us from, it seemed, three directions …we went back and got the men. It was hard to make them move, they were so badly broken. Our leader was shot before we arrived and the strain had sent two other officers mad. I and another new officer took charge and dug the trench. We were being shot at all the time. The wounded and killed had to be thrown on one side. I refused to let any sound man help a wounded man. The sound men had to dig. Many men went mad. I took it on myself to insist on the men staying, saying that any man who stopped digging would be shot. We dug on and finished amid a tornado of bursting shells. We got away as best we could …again we were cut off and lost. I was buried twice and thrown down several times – buried with the dead and dying. The ground was covered with bodies in all stages of decay and mutilation, and I would, after struggling free from the earth, pick up a body by me to try to lift him out with me and find him a decayed corpse. I pulled a head off RR – was covered in blood. The horror was indescribable.

Not long after conveying these nightmarish scenes, Alec, in his final letter days before he was killed, wrote home…

Before going into this next affair, at the same dreadful spot, I want to tell you, so that it may be on record, that I honestly believe that Goldy and many other officers were murdered on the night you know of, through the incompetence, callousness and personal vanity of those high in authority. I realise the seriousness of what I say, but I am so bitter and the facts are so palpable, that it must be said. Please be discrete with this letter – unless I should go under.

Less than 400 days before, Alec had written to his father rationalising his decision to enlist.

I hope that you will be proud to think that you have two sons, who were never fighting men, who abhor the sight of blood and cruelty and suffering of any kind, but who yet are game to go out bravely to a war forced upon them.

Pozières was the origin of much understandable criticism and bitterness against the British commander, Sir Hubert Gough, who was seen as impetuous, a poor planner and “not quite sane” according to at least ANZAC commander. For Alfred and the 23rd battalion, Pozières was quickly followed by another horrific battle at Moquet Farm. By the end of July 1916 these these two conflicts had cost the lives of over 90% of the men of the 23rd!

In October Alfred was promoted to the rank of Corporal after another Corporal named Mindenhall ‘died of his wounds’.

After manning the front lines throughout the bleak winter of 1916-17, the battalion’s next trial came at the second battle of Bullecourt in May 1917. Following the failure of the first attempt to capture this town by troops of the 4th Australian Division, this new attack was heavily rehearsed. The 23rd Battalion succeeded in capturing all of its objectives and holding them until relieved, but, subjected to heavy counter-attacks, the first day of this battle was the battalion’s single most costly of the war: Ordinary Rank numbers were reduced from 1000 to 647, Officer numbers reduced from 40 to 26 in 24 hours.

While in reserve at Warloy, General Birdwood presented the 23rd battalion with ‘medals and ribbons’ on June 6th and on the same day Alfred was transferred to the No. 2 ‘B’ Group Headquarters at Rollestone in England. Since the focus of the war had shifted to the Western Front in 1916, so headquarters and AIF camps for training new reinforcements moved to the Salisbury Plains in England – one of these camps was at Rollestone in Wiltshire.

Alfred attended a course at the Southern Command Signalling School at Wyke Regis, Weymouth for about 6 weeks and qualified as an “assistant instructor”. Signals personnel are responsible for maintaining communications between units. In the days before electronic communications, this was achieved through the use of flags, heliographs (mirrors used to reflect sunlight) and dispatch riders and runners. Signals personnel are known as “signallers” and, since their job requires much talking on various communications devices, they have been nicknamed “chooks”.

There is nothing in Alfred’s military record which explains why he was transferred from the Western Front to commence a signalling course in England. While there is no direct evidence that he had been injured, other war documents indicate some shell shocked or gassed troops were sent back to England to recuperate and they sometimes assisted in training the recruits arriving from Australia or did courses to increase their skills.

The hill at Fovant with some of the regiment emblems still visible – see red rectangle area in large photo above

As a trained sIgnaller instructor Alfred was transferred to the 2nd Signalling School at Fovant, about 15 kilometres west of the town of Salisbury. After about 2 months on the Signalling school staff at Fovant Alf must have been declared fit for service once more and /or a group of reinforcements were now trained and ready to join the 23rd battalion. He was transferred back to his Unit in France. From Southampton Alfred disembarked at Havre on 31st January 1918 and rejoined the 6th Brigade at Quesques on 5 February 1918. The battalion had recently been moved away from the front and were billeted at Quesques, about 40 miles south of Callais. The whole battalion had recently been treated en masse for “trench feet” – a painful condition caused by the constant cold and dampness in the trenches and which can lead to gangrene and amputation.

On February 15th the 23rd Battalion lost an inter-battalion football match to the 22st Battalion by 2 goals. The event was reported in the Battalion newspaper “The Twenty Third” …

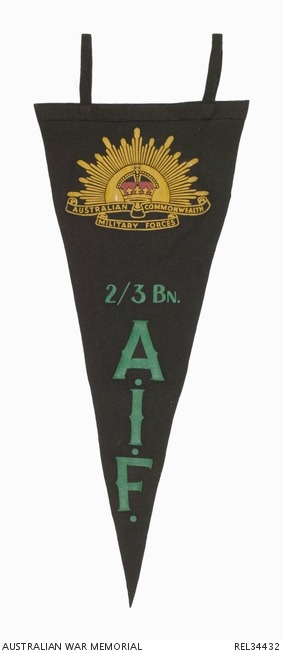

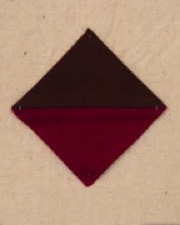

The match was played in almost a quagmire. It is wonderful how either team stayed the four quarters. A dirty bit of play was indulged in by “he of the broken nose” …its a pity. as the other 17 men were sports. Want of practise was the disadvantage plainly visible on the part of the chocolate and brown diamonds (see Battalion Colour Patch).

A few days later the whole battalion had “dental parade” with every man having a dental inspection. Five days after the first game, the 23rd played the 24th battalion in another football match; this time losing by 4 goals. The newspaper reported that the 23rd team let the final quarter slip away as they “were in a fagged condition”.

During March Alf’s Battalion marched eastwards for 4 days, covering the 50 miles from La Verval to Romarin. In April they moved to Millencourt where they held front lines. In May the battalion captured the town of Villes-sur-Ancre and reported the ‘foul play’ of a German Officer who surrendered and then subsequently fired on the Lieutenant who who was taking him prisoner. The regimental newspaper celebrated the third anniversary of the Battalion sailing from Melbourne with the following….

As we enter the fourth year of active service we do so with the full determination to to uphold the laurels of the past, and perhaps add to the list. “Forward, Undeterred” is our motto and while looking for the silver with which every dark cloud is said to be lined, we do so with that finest of English words – HOPE – uppermost in our minds, and the belief that the next 8th May will see us back on the other side of the world.

In June the battalion suffered “an epidemic of PUO” (Pyrexia Of Unknown Origin – commonly called ‘Dog’s Disease’ or, later, ‘Trench Fever’. Trench fever infected a total of approximately 450,000 allied troops, could put a soldier out of action for a week and was eventually found to be caused by the excreta of lice.

Alfred was again wounded in action on 18 August 1918. The battalion diary for that day contains much greater detail than usual. The 23rd was stationed in front line trenches at Herleville and were ‘mopping up’ after a successful attack on the German position the previous night. The objective was to capture a point called ‘the Crucifix’ held by the Germans.

Owing to our few men on the front, the taking of prisoners was a secondary consideration and a great many of the enemy were killed. This shortage of men also accounted for the escape of a good number of the enemy. At 4.20am B Coy. who were in position proceeded to comb north along SAURIAN ALLEY and linked up with C Coy. After dealing with 1 Machine Gun and crew and dispensing one bombing party, connection with C Coy.’s right flank was complete. Our casualties up to this period were very light. Success signals were observed on our front at 4.40am. Closely following this an S.O.S. was observed to go up on our left flank opposite another unit. Artillery were then requested to continue with protective barrage. Our captures included 1 German Officer, 10 OR’s, 2 heavy and 6 light machine guns. Close liaison with neighbouring unit enabled us to quickly ascertain that the CRUCIFIX was still in the enemy’s hands.

Although the CRUCIFIX was captured soon afterwards, Alf had been injured and I presume was part of the ‘very light’ casualties mentioned above. Estimated German casualties in this

action were 25 killed and 30 wounded. Corporal Alfred Quennell was removed from the front line trenches to the 90th Field Ambulance. He was admitted with a gunshot wound to the fingers of his left hand. The following day Alf was processed through the 61st Casualty Clearing station and transferred by ambulance train to the 5th General Hospital, about 150 miles west, at Rouen. 3 days later Alf was “invalided to England”. The next day, on 23 August, Alfred found himself admitted to the ‘Monyhull’ Section of Highfield Hall at the 1st Southern General Hospital in Birmingham.

By Spring 1919, some 130,000 military casualties had been treated in the Birmingham war hospitals. The majority had suffered wounds or sickness on the Western Front.

Alfred spent about 3 weeks at Monyhull before being transferred to the 1st Australian Auxillary Hospital, known as ‘Harefield House’ in Middlesex, on 14 September 1918. While at ‘Harefield’ Alfred went on furlough for about 2 weeks. On return from leave on 4 Oct 1918 Alf was classified as Category B1, a1: essentially meaning that he was not fit for active service but was capable of employment in base unit or sedentary positions. As such Alf was sent to No.1 Com. Depot at Sutton Veny Camp, back in Wiltshire – close to where he had trained as a signaller about a year earlier.

The armistice between the Allies and Germany was declared on 11 November 1918. Alfred married English girl Phyllis Constance Hamilton on 22 February 1919 at the All Saints Church in Worcestershire, which is about 40 kilometres south of Birmingham where I suspect Alfred may have met Phyllis during his recuperation time at ‘Monyhull’, Highfield. It would not be surprising to find that Phyllis was either a nurse or red cross worker at Highfield, although I have yet to find any evidence supporting that supposition. Alfred continued with the Pay Corps and was promoted to Sergeant late in April 1919, only days before his 23rd Battalion was disbanded in Belgium on 30 April.

On 4 June 1919, Alfred embarked for Australia on the SS Bremen, arriving in Melbourne on 25 July (did Phyllis sail with him?). He was discharged from the AIF on 23 September 1919. Alfred and Phyllis settled back intoMelbourne civilian life, initially at 25 Beach Ave and later at 7 Small St, Elwood.

On 15 August 1920, Alfred and Phyllis had a daughter named Mary Beatrice – she was to be their only child. In 1943 Mary married another returned soldier named Charles Gilbert. Lieutenant Gilbert was born in London but had fought in the second World War with the AIF’s Second Field Regiment in Greece, Crete, Libya and later, New Guinea. During the battle for Bardia in Libya against the Italians in January 1941, Lt. Gilbert (who was a signaller like his father-in-law Alfred) earned the Military Medal for personally repairing the communication lines while under shell and machine gun fire. In recommending him for his medal, an officer wrote:

…his courage was in keeping with the highest traditions of the signallers and his action in sustaining communications kept the battalion in action

Lt. Gilbert was one of the twin sons of well known war sculptor Lt. Charles Web Gilbert who has work in the Tate Gallery London and who produced many war dioramas and the well known statue of Mathew Flinders outside St. Paul’s Cathedral in Swanston St, Melbourne.