Hobart Town 1869

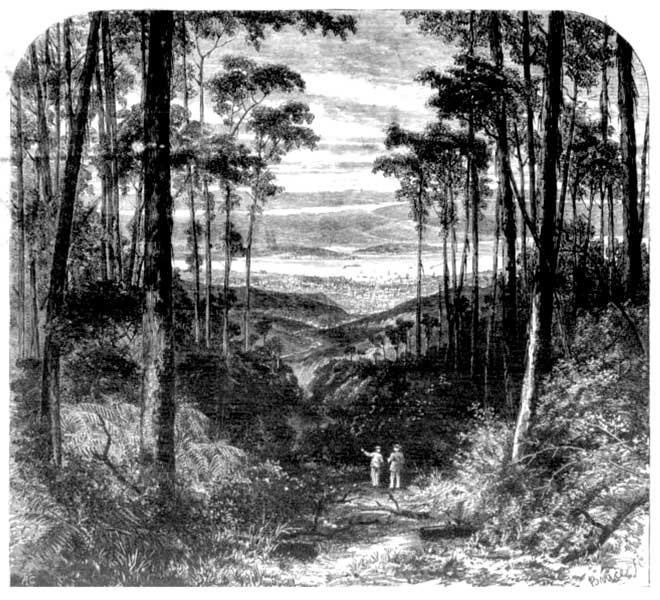

HOBART TOWN, FROM MOUNT WELLINGTON

As personal impressions with regard to a place afford the best materials for describing it, this writer’s own impressions, derived from a recent trip to Tasmania, will be appropriately serviceable for a description of Hobart Town and its environs. The number of visitors to Tasmania this season is observed to be much greater than usual and is likely to increase year by year as the attractions to be found on the other side of the Straits become more generally known. I saw lots of Victorians when I was there. I found all, with one exception, delighted with the ‘tight little island’ and for my part I was always ready to join heartily in the chorus of admiration.

The exceptional individual had not a word to say in praise of the delicious climate, or of the beautiful scenery. Nothing seemed to strike his eye but the dullness of the place, and this so haunted the poor fellow that he kept moaning incessantly.

There is nobody to be seen in the streets, he said, nothing doing, no life, no amusements of any kind, there is no theatre to go to ; what am I to do at night in such a place as this? I can’t stay here, I’ll go back by the next steamer,

and go back he did. Compared with Melbourne, Hobart town is rather dull, especially to one who has no resources within himself. I can’t say that I found it dull. There was less excitement, to be sure, than I had been accustomed to of late, but why complain of that when it was the very bustle and turmoil of Melbourne life that I wanted to get away from for awhile. I felt that I needed rest for my jaded brain, something if possible to exhilarate my spirits, depressed by the sweltering heats and foul smells of Melbourne, cool breezes to brace my nerves, novelty and beauty of scenery to refresh and divert my eye and all these I soon found that I had a better chance of getting on the shores of the Derwent than anywhere else in the southern hemisphere.

From whichever side the landward or the seaward, you approach Hobart Town, the view is such as to fascinate your gaze. It was from the deck of the steamer which brought me direct from Melbourne that I first saw that view, and I shall never forget it. It was morning, and I was hardly in a mood for enjoying anything, having passed the night in trying to get sleep stretched on the saloon table and breathing a deoxygenised and horribly tainted air. In vain I heard some of my fellow passengers remark that we had passed Tasman’s Pillar, and were approaching Cape Raoul. I was too stiff and listless to get up even for the sake of obtaining a glimpse of that famous headland.

When we had got fairly into the estuary of the Derwent, and the sea had become perceptibly smoother I managed to crawl upon deck in time to get a near view of the rocky islet named after Lady Franklyn, and recently presented by her to the Acclimatisation Society. The next point was the lighthouse, called the Iron Pot, and that point being turned we were in an inland sea, Lady Franklyn’s island and Bruni island appearing to shut out the ocean behind us. We were borne on the placid surface of what had every appearance of a lake, about two miles wide and seven miles long.

On either side we saw long extending and wooded hills, with many a cove here and jutting promontory there, and with ranges beyond ranges filling up the back ground. The nearer slopes of the hills were thickly studded with villas and farm houses, with corn fields, gardens and orchards stretching to the waters edge, and before us Hobart Town nestling at the foot of Mount Wellington, whose head was enveloped in cIoud. The water, wide enough and deep enough to hold a fleet, permits the steamer to sail close up to tho town, and, placid as a mirror on the morning of our arrival, reflected all tho glorious beauty of land and sky. To me the scene was enchanting ; sleeplessness, weariness and sea-sickness were all forgotten. The first sight of a large town is apt, especially if possessed of many remarkable features, to suggest a comparison with other towns you have seen. Looking at Hobart Town from the dock of the steamer, I was at once reminded of Geneva. The estuary of the Derwent, which, as already remarked, has here all the appearance of an inland sea, may be regarded as a miniature Lake Leman. The town, extending over an undulating surface and sloping upwards from the water’s edge, discloses tier above tier of streets and houses, like the city of Calvin ; while Mount Wellington, just behind, is, in its position and square massive grandeur of form, wonderfully like Mount Saleve. The comparison must be confined, of course, to these external features.

When you get into Hobart Town you are struck by its entirely English aspect. There is an air of maturity about the place which presents an agreeable contrast to the architectural rawness which vexes one in Melbourne. The people have dispensed with weatherboard long ago, they have never tried galvanised iron, they don’t need brick or stucco for they have plenty of admirable lightly-colored freestone and every house is built of it. There are few buildings of an imposing style ; solidity and comfort seem to be the aim and very comfortable indeed many of them look, especially the villas in the outskirts, few of them being without a garden enclosure full of fruits and flowers and fewer still without an ample prospect of mountain, wood and water. Macquarie street, occupying a long stretch of gradual ascent from the quay to a gorge at the foot of Mount Wellington, contains several public buildings, and may be considered the main street in the town.

When you get into Hobart Town you are struck by its entirely English aspect. There is an air of maturity about the place which presents an agreeable contrast to the architectural rawness which vexes one in Melbourne. The people have dispensed with weatherboard long ago, they have never tried galvanised iron, they don’t need brick or stucco for they have plenty of admirable lightly-colored freestone and every house is built of it. There are few buildings of an imposing style ; solidity and comfort seem to be the aim and very comfortable indeed many of them look, especially the villas in the outskirts, few of them being without a garden enclosure full of fruits and flowers and fewer still without an ample prospect of mountain, wood and water. Macquarie street, occupying a long stretch of gradual ascent from the quay to a gorge at the foot of Mount Wellington, contains several public buildings, and may be considered the main street in the town.

Here are the banks, several schools, some churches, of which one is St. David’s, the mother church of the country; here are the Government offices and some of the law courts; and here is the new Town Hall, chaste in its external simplicity of design, elegant and commodious within. Between the Government offices and the Town Hall is a small space of ground, to which some interest attaches. A public garden now, it was the site of the old Government House, where dwelt a succession of Governors, from Collins down to Sir John Franklyn and on the very spot now occupied by Franklyn’s monument, stood the gubernatorial chair in which they used to sit when in council. On the opposite side of the street, but a little way higher up, is the house which has the honor of being the first erected in Hobart Town, now more than sixty years ago. I found out that the house in which I lodged was the third erection ; it is now a boarding-house, and a very comfortable one it is, just the sort of place for a stranger to feel at once as if he were among friends— to feel at home, as we may say. Every one, I am sure, who has been at Mrs Langley’s, will confirm my opinion.

Parallel to Macquarie street is Liverpool street, which is the Bourke street of Hobart Town, being the quarter affected by drapers, grocers and tradesmen of various kinds, and presenting a crowded scene on Saturday nights. Ordinarily the streets are quiet enough – there is no hurrying to and fro’ as if business were urgent ; no jostling as in Bourke street, Melbourne ; no fluttering of silks and gauzy robes as in Collins Street ; no appearance of young men anywhere ; no lorries or ponderous vans in the thoroughfares ; no gay equipages with high-stepping horses ; no fear of being run over by cars dashing along at a mad pace. The only vehicles to be seen are a few anti-deluvian looking broughams on the stand, or crawling about at a snail’s pace.

There is one vehicle, by the bye, which I ought not to forget, and that is the mail coach which runs between Hobart Town and Launceston. It was always an object of interest on its arrival or departure, none of your leathern lanky concerns, after the American pattern introduced by Cobb & Co veritable old English stage coach with its flaming yellow and red paint, royal arms, inside and outside, a driver who cracks the whip in the genuine English style; and a guard who wears a scarlet coat, and blows the orthodox horn and all the rest of it. Occasionally I took a stroll down to the wharf to see what was going on; but there, appeared to be as little doing in that quarter as in the streets except on the arrival of the steamer from Melbourne or its departure, when crowds of people— used to flock to the jetty to welcome friends or bid them goodbye. Three whalers that had come to port for repairs and stores, two London ships, some half dozen coasting schooners and sloops, constituted the shipping. The smooth surface of the estuary was broken only by a passing skiff or the mail steamer which plies, between Sullivan’s Cove and Kangaroo Point. The warehouses seemed tenantless, and the traffic, such as it is, consisted of shingles, wattle-bark and fruit.

These deserted streets and tenantless warehouses have a tale to tell, and whenever you enter into conversation with the people you have the tale repeated. They are downcast as to the prospects of the place. The first question they put to a visitor is, ‘What do you think of the colony?” If your reply is favorable, as it is sure to be, they look uncommonly pleased. Then they tell you that it is not what it used to be and you hear tales about the convict times, and the Port Phillip times, and the gold fever times ; and with lamentations over the past are mingled speculations as to whaling, and gold finding and railway projects; and the conversation, if addressed to a Victorian, will wind up with the remark :—

You have sucked the life out of us, and now you must annex us to your country ; that is if, after all, we can submit to be annexed.

Lying a little way out of town, in a northwest direction from it, are several places which the stranger will be sure to visit, such as Government House, the Botanical Gardens, the village of New Town and Risdon’s Ferry. You have the graceful windings of the Derwent in view, all in the way. Mount Wellington lies behind; but you hardly miss it, as you have the abrupt front of Mount Direction before you on the right, just across the river, and the curiously shaped Mount Dromedary on the left, forming a noble frame for the charming picture presented by the valley of the Derwent. Government House is a fine baronial building occupying a position on one of the slopes close to the town, and commanding a full view of the harbor, the bay and the hills on either side right out to the open sea. The gardens extend down to the water, and, as I saw them from the windows of the hall, presented a very gay appearance, which was due specially to the presence of an immense bed of scarlet geraniums. The Botanical Gardens are quite contiguous, a hedge being all that separates them from the grounds of Government House. A better site for a public garden could not be found than this cosy nook by the river’s side. The grounds are well laid out and tidily kept. At New Town I first saw our old English friends, the hawthorn and the sweet briar ; not solitary shrubs as we may see them occasionally in Victoria, but forming regular hedges, thick, massive and impenetrable, with green lanes between; I became familiar enough with the sight afterwards, for it is one of the characteristic features of the country. Among the many habitations in New Town, beautiful for situation and prospect, my attention was specially directed to two — the Orphan Asylum, on a fine elevation at the foot of the ranges, and the villa of Bishop Nixon, a humble cottage, but displaying taste and cultivation in the grounds which overlook a little bay affording convenient anchorage for his yacht. A mile or two beyond we come to Risdon Ferry, which possesses some interest as being the spot where the first settlement was made out of which grew Hobart Town and all the civilisation of the island.

About twenty-five miles up the Derwent is New Norfolk, remarkable for its hop grounds, and for the salmon ponds six miles farther on. To visit these occupies two days at the least ; you may go on one day up the river in a small steamer, and return the next by the coach along, the river’s bank. Pleasant it is, as you sail on the broad bosom of the Derwent, to watch the changes of view at every curve, the play of light and shadow on the wooded hills and sleepy hollows, the bright patches of cultivation and the comfortable homesteads on many a sunny knoll.

Of excursions there is no end; one day it is a sail across the bay to Kangaroo Point or Rosny, another day it is a drive to Brown’s River on the opposite side of the estuary, or a trip in a steamer to the Huon district, noted for its strawberries and its splendid timber. To dilate on the pleasure which these various excursions yielded is tempting; but diminishing space forbids, and I must hurry on to the best excursion of all, which was to the top of Mount Wellington. A toilsome ascent it was, but the toil was well repaid. The distance is not long taking it lineally, being about seven miles from the city to the summit ; but it is a stiff climb and awfully rough at some parts. No one should undertake to walk the whole way unless possessed of full bodily vigor and accustomed to up-hill work. It is usual for three or four to join together, and engage a vehicle to convey them as far as the road permits. This was what we did, and by setting out at six o’clock in the morning we were enabled to get back by three in the afternoon. The vehicle carried us in about an hour or so to a humble hostelry built for the accommodation of visitors, and there we left it till our return, and set out for the summit on foot.

The road so far is good for a mountain road, being, in fact, the highway to the head of the Huon River. Winding in somewhat zig-zag fashion along one of the gorges of the mountain, it prepares you gradually for the wild beauty and grandeur in store. On leaving the vehicle you commence at once to feel the stiffness of the ascent. A narrow pathway stretches upwards before you between the trees— so straight and so steep that it looks like a line dropped from the clouds. An hour’s trudging in Indian file up this path brought us to the ‘Springs,” so called because here springs the water which supplies the city beneath. In the neighborhood of the “Springs” is a hut where refreshment may be obtained ; a little farther on are some ice-houses, in which a Hobart Town confectioner stores ice from winter to summer. As we had brought provisions with us, we did not trouble “the old man of the mountain,” as the hut-keeper is called, but pushed on till we reached a convenient spot known to some of our party, and there we rested and had our breakfast. It was a little open space in the forest, strewn with boulders, and through the interstices, which were somewhat wider than usual, between the tall gum trees we had a glorious vista right down to the city and the bright waters of the Derwent.

Our breakfast was needed, both on account of what we had done, and of what we had to do. Steeper and rougher was the track, our course being often impeded by boulders and fallen trunks ; the trees got scantier, and more stunted ; and lichens and mosses took the place of the ferns, the scarlet waratahs, and many other blooming flowers, which we had seen in abundance lower down; the air, too, was sensibly rarified, and considerably colder. Beyond the limit of tree vegetation, and just before you reach the summit, lies a peculiar region, called by the Hobart Town folks the “Ploughed Field.” Imagine a collection of boulders, each as large as a stockman’s hut, thrown pell-mell over each other, and covering a space some acres in extent, and you will have an idea of the scene, and understand how it has got its name. To get over it requires some goat-like agility ; once over it, you are on the plateau, and in half an hour more you are on the highest point, 5,000 feet above the sea, and looking around you on a magnificent prospect, vast and varied ; now beautiful, as the sun flashes on the city below, or on the river curving and widening out into the estuary, and from that into the ocean, whose islands, or rather promontories and peninsulas looking as if islands, “on its bosom float like emeralds chased in gold ;” now sublime, as the sun gets behind clouds and casts purple shadows over the range beyond range of mountain tops that stretch right across the island.

I turned away from the magnificent view in a thankful spirit; for had I not added to the picture gallery within the mind, where hung recollections of some of Europe’s fairest scenes, another of nature’s own paintings, not unworthy of a place beside them.

What think you of the tight little island now, asks a friend ; ‘are you satisfied that you selected it for your ‘out ‘ ?” Perfectly, my friend ; and though I may not be able to return myself, I advise everybody to go.