A Lode of Growed Toad

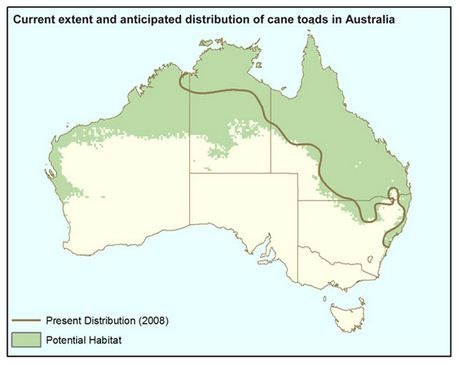

The cane toad, Bufo marinus, is a very successful species which has invaded the Australian environment since its deliberate introduction in 1935. The cane toad was introduced to northern Queensland to control the greyback cane beetle, Dermolepida albohirtum, a pest of sugar cane fields. The toad did not, however, have any effect on the beetles as the two species inhabit completely different parts of the crop. The cane toad has since spread south and west throughout Queensland and across state borders into New South Wales, the Northern Territory and will soon spread into Western Australia.

Toad V. Cane Beetle – Experiment For Cane Fields

Toad V. Cane Beetle – Experiment For Cane Fields

BRISBANE, Friday

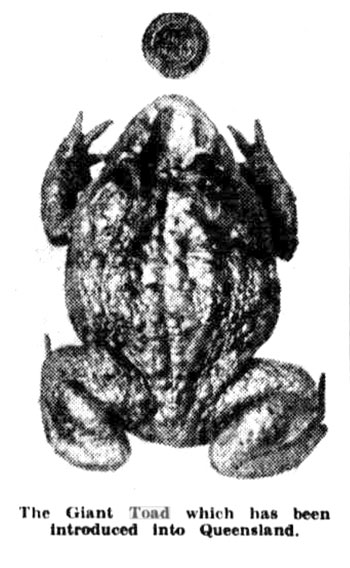

A new war is about to be waged in the northern cane fields by the giant American toads against the grey back cane beetle. The first consignment of one hundred arrived from Honolulu this week and will be taken to the Meringa experimental station for breeding purposes and later be distributed throughout the affected districts. These toads, which are 6 to 8 inches in length, of a brown colour, have done splendid work in, keeping down insect pests in the Barbados, West Indian Islands and Hawaii.

Bowen Independent (Qld. : 1911 – 1954), Friday 21 June 1935, page 1

Toad Visitors To Combat Cane Beetle

Toad Visitors To Combat Cane Beetle

QUEENSLAND’S toad population is not a large one, but it is unlikely that the arrival here recently of a hundred giant toads from Honolulu will be more than noted by the local types. These strangers have come on invitation but not for pleasure. The greyback cane beetle is to be the subject of an offensive and it is hoped that they may prove useful in its control. Toads live a long life, frequently as long as 10 years. Sometimes they are said to be found alive in rocks, but no one has been able to prove this, and several experiments in forced imprisonment have been disastrous for the toad. There are many strange varieties. The Surinam toad carries its eggs on its back under a protective cover. Another has shovel-like hands with which to burrow, and sonic live entirely in trees.

Telegraph TUESDAY, AUGUST 13, 1935.

The Giant Toad Eliminating Cane Beetles

Innisfail, July 10

Considerable interest was manifested at Innisfail at the recent announcement in the “Cairns Post” that a number of specimens of the Giant American Toad (Bufo marinus) had been sent to Meringa Experiment station, near Cairns, for propagation and subsequent distribution in the far northern cane areas for the purpose of fighting the cane beetle pest.

Mr. R. W. Mungomery, of the Sugar Bureau, recently pointed out that certain people had raised the question of the toads possibly proving a nuisance owing to the noise they will make. Their call (says Mr. Mungomery) is not objectionable, and certainly not as loud nor as shrill as that of many species of frogs which are indigenous to Australia. It has sometimes been described as being similar to the distant sound of a motor cycle, of that regularity, but more musical.

No Black Marks

Mr. Mungomery adds: “To others who scent a ‘nigger in the woodpile’ and suggest the possibility that the toad will in turn itself become a pest, we can point to the fact that nearly a hundred years have elapsed since it was first introduced into the Barbados, and there it has no black marks against its character. Experience with it in other West Indian islands and in Hawaii certainly point to the fact that no serious harm is likely to eventuate through its introduction into Queensland.

Not Edible

“One important note of warning must be raised. This toad, though large, is not the edible species of frog, and it must not be eaten. The glands at the side of its head secrete a digitalis-like poison, adrenalin, and other more obscure poisons, and if the toad is eaten the net effect of these poisons is apt to have a very serious effect on the heart. Whilst I was in Hawaii a young Filipino child died, and it was alleged that she died as a result of her parents giving her portion of a toad to eat. Whether these facts are true or not is difficult to ascertain, but this example should be sufficient warning to deter anyone so minded towards a dish of the famous French delicacy to defer it until the edible variety of frog is available and certainly to give Bufo a wide berth.”

Cairns Post (Qld. : 1909 – 1954), Friday 12 July 1935, page 14

Giant Toad Comes Marching South

By IAN M. BROWN

EVERYTHING about it – its very name is vile. Its huge belly is always distended. The angry glitter in its eye revolting. It has legs but they do not raise its carcass above the mire. It has eyes but they do not welcome light-its bane. Its habitation is filthy. Its habits disgusting. Its colour dingy. Its breath foul.

Thus ran an old tirade against the toad, a giant variety of which, according to recent reports, is out of hand in Queensland and getting closer to New South Wales.

Thus ran an old tirade against the toad, a giant variety of which, according to recent reports, is out of hand in Queensland and getting closer to New South Wales.

The giant American toad, Bufo Marinus, was introduced into Queens-land from Hawaii in June, 1935, by the Bureau of Sugar Experimental Stations, with the object of assisting in the natural control of the greyback beetle pest which, in the grub stage, is responsible for the loss of thousands of tons of sugar cane every year.

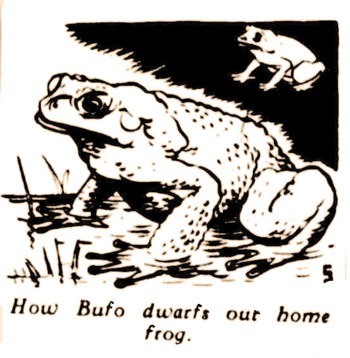

This toad, which hails from Mexico, is truly a giant among toads. Specimens with a body length of nine inches and a mouth large enough to swallow small birds, have been captured in that country.

It has a rough skin studded with large pores. The colouration is variable, ranging through various shades of brown. Its underparts are a dingy white or yellow. Mature males have low, spiny tubercles on their back. When provoked they eject a milky poison from large glands in clusters forming the tubercles.

In the first year, 60,000 toadlets were liberated in suitable localities, adjacent to grub-infested cane areas, in the Cairns-Innisfail districts of North Queensland only, on account of restrictions imposed by the Commonwealth Government. Egg strings were also placed in streams and in water holes.

In the first year, 60,000 toadlets were liberated in suitable localities, adjacent to grub-infested cane areas, in the Cairns-Innisfail districts of North Queensland only, on account of restrictions imposed by the Commonwealth Government. Egg strings were also placed in streams and in water holes.

‘THE first Australian-born generations commenced to reproduce in the early summer months. In the first year it was estimated that 1¾ million eggs were laid in captivity, and toads were recovered a mile away from the nearest point at which they had been liberated as toadlets. Individuals up to 5¼ inches in length were found.

After their feeding habits were studied and it was noted that they ate garden insect pests and cockroaches, restrictions were lifted, and in 1938 toadlets were introduced to all sugar areas in Queensland, where grubs caused noticeable injury. Prolific breeding followed, and the toads scattered far and wide. They were observed eating greyback beetles under natural conditions during beetle flight.

By 1939 it was considered that the toads had reached peak populations in areas where the original releases were made.

A systematic examination of the stomach contents of the toads was carried out to determine what constituted their food in their new habitat. Apart from greyback beetles, there were found other cane pests, including the very important borer weevil.

The Bureau’s report of 1940 pointed out, however, that on the score of observations in the field, and because grub damage had increased that year in areas where toad population was high, it was evident that the number of beetles destroyed by the toads was relatively small compared with the number that were nightly on the wing. Evidence seemed to indicate that the toad might be of more use in the destruction of the beetle borer.

The Bureau’s report of 1940 pointed out, however, that on the score of observations in the field, and because grub damage had increased that year in areas where toad population was high, it was evident that the number of beetles destroyed by the toads was relatively small compared with the number that were nightly on the wing. Evidence seemed to indicate that the toad might be of more use in the destruction of the beetle borer.

Always seeking out the damp spots, the toads invaded household gardens and wood heaps, and in the wet areas of North Queensland are now to be seen almost everywhere.

The unexpected sight of one of these ugly amphibians is startling, but it usually makes off, seeming to run rather than hop. Roads, where they pass close to tropical vegetation, are littered with the bodies of hundreds of these creatures, victims of passing motor cars.

Although their habits are nocturnal they cannot see in complete darkness and seem to be attracted by dim light. Around Innisfail at times they are seen in such numbers on the roads, near street lights, that the whole surface appears to be “alive.”

There is no record of humans being affected by their poison, but dogs and cats suffer temporarily.

A DOG catches the toad by the back, and although the dog’s mouth is not in contact with the toad for more than an instant he immediately loses interest. He refuses water, and within a minute or so shows signs of general paralysis and weakness. He writhes and whines in pain, but after an interval of about 20 minutes is quieter and recovers completely without lasting effects.

A comprehensive series of experiments were carried out by the bureau to test the effect of possible contamination of domestic fowls’ drinking water by toads bathing in it over-night and the feeding of young toads to poultry. The tests were severe, but no ill effects were noticeable. One fowl ate no fewer than 142 small toads in little more than an hour yet remained quite normal.

Toads have been observed feeding on small grasshoppers so it would appear that they will be useful in checking those pests.

Whether they will become pests themselves remains to be seen. Since the appearance of the toads in south Queensland, apiarists have asked the Department of Agriculture to keep them out of New South Wales because they fear they will develop an appetite for bees.

Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), Saturday 2 August 1947, page 9

“MR. TOAD” (X.O.S.)

By Dinah Stewart

MOST PEOPLE know of the Cactoblastus beetle, which, contrary to expectations, didn’t solve the prickly pear problem, after all. The Bufo  toad’s story is similar. Legend claims him: monster sized, chasing chickens and frightening small children returning home from school.

toad’s story is similar. Legend claims him: monster sized, chasing chickens and frightening small children returning home from school.

Hailing from South America, his mighty appetite, and taste for sugar-cane beetles, brought him popularity. His services were eagerly conscripted by cane growers. He colonised in French Guiana, the West Indies, the Philippines. In 1923 a Queensland Government representative visiting Puerto Rico, observed these toads, eating their heads off. Their appetites were enormous. Their digestion appeared sound, and they were busy devouring the grey back sugarcane beetle. Clapping his hands gleefully, the impressed delegate left with a large consignment of toads,

Bufo

It was hoped that these blokes would eliminate grub damage in the Queensland canefields. They were liberated first in Cairns, Gordonvale, and Tully districts. Observing their appetites, other cane-growing districts clamoured for toads, too.

Today toads and toadlets are plentiful. How they breed! The pools along the little Mulgrave harbour thousands of them. One conscientious female, under observation, produced 16,000 eggs at a sitting, and attempted a similar feat some months later. Obviously a toad with a large performance.

In Appearance

Bufo Marinus, the gentleman in question, is just like any other toad, except that he is far too large. Seated on a bread and butter plate he would get cramps. On each side of his head Bufo wears a poison sac. These sacs contain Digitalis and Adrenalin, and are calculated to make any interfering animal spit. Toad would feel pretty silly if his system failed him. He has more party tricks. His song resembles the sound of a motor-bike. This has caused many an un-suspecting couple to leap for safety from the roads at dusk.

A toad with these talents would probably prosper anyway, but under Government patronage he just couldn’t miss. Unfortunately he has not fulfilled his obligations. Like the Cactoblastus beetle he has eaten more than the poor grub he was intended to destroy.

Proud of toad at first, a note of discontent later crept into the pages of the Queensland Agricultural Journal. Toad could, and did, eat slugs, scorpions, and ants; no one worried. Gradually, it appeared that toad although voracious, was eating a relatively small quantity of beetles compared to those remaining on the wing.

His attention had turned to bees. Lolling in the sun outside the hives he waited for the honey-laden bees’ return. Those, who evaded him and whizzed past to the safety of the hive gained nothing. Bufo extended a lengthy tongue and sucked out hundreds at a meal. Life’s just too easy for some people.

His attention had turned to bees. Lolling in the sun outside the hives he waited for the honey-laden bees’ return. Those, who evaded him and whizzed past to the safety of the hive gained nothing. Bufo extended a lengthy tongue and sucked out hundreds at a meal. Life’s just too easy for some people.

Striving to provide sanctuary for their swarms, grim-faced Queensland apiarists raised their hives two feet from the ground. Wire-netting barricades surrounded the entrance to each hive. This made them very difficult to move. Discontent reigned. Even a bee gets tired of the same old view. Appalled, the Commercial Apiarists Association of N.S.W. (and I mean beekepers), requested the Commonwealth Government to take action in preventing the rapacious toad’s appearance in other States. Fencing in Queensland is a simple solution to this problem.

Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), Friday 11 May 1951, page 10

1 Response

[…] Just in case you missed the connection, the big ugly toads mentioned above – the ones with all that serotonin neck poison are….. yep, our good old Cane Toad. […]