Leucotomy

Leucotomy (or lobotomy) is an obsolete treatment for schizophrenia – the surgical ‘interruption’ of nerve tracts to and from the frontal lobe of the brain – usually with the aim of alleviating or ‘curing’ the mental illness. It often resulted in marked cognitive and personality changes. The originator of the procedure, Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz, shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine of 1949 for the “discovery of the therapeutic value of leucotomy in certain psychoses.”

António Egas Moniz

The use of the procedure increased dramatically from the early 1940s and into the 1950s; by 1951, almost 20,000 lobotomies had been performed in the United States alone. The procedure was always controversial and began to decline in the 1950s especially after the arrival of psychotrophic drugs such as chlorpromazine (Largactil).

My interest in this subject stems from my experience of psychiatric nursing of several patients in the 1970s (including a teenager) who had had a leukotomy. The following article is from 1953.

Leucotomy causes medical storm in Britain. Many doctors in Britain doubt benefits of brain operation

By Dal Stivens from London

One of the most violent controversies in British medical circles for many years is now raging behind the scenes. The controversy, which touches religious, moral and spiritual issues, concerns leucotomy, a brain operation performed on the mentally ill. So far the dispute has been fought mainly in the hospitals and in the pages of the British Medical Journal and The Lancet, but it threatens to pour out into the streets at any moment.

Some doctors have asked that the operation be banned, or at the very least be rigidly controlled; a few clergymen have claimed that the operation damages the soul. Already, one country, the Soviet Union, has banned it. Echoes of the same controversy have been heard in Australia in recent months, when a bill to legalise leucotomy was before the NSW Parliament. After considerable debate and several amendments the bill was passed.

The NSW Act provides for leucotomy operations of a defined nature to be performed on mental patients in State mental hospitals, but requires the consent of the patient’s spouse, parents or guardians before being performed. If consent is unjustifiably withheld, the Master-in-Lunacy may order the operation after a consultative medical committee has reported on the case.

First leucotomy operation under the new Act in NSW was arranged a few weeks ago for a woman in a State mental hospital. The woman has been tied to a mattress on the floor in a strait jacket for two years. She had been stronger than any four female nurses and, though the patient is a woman all personal treatment and care had to be done by male attendants.

Leucotomy was first carried out in 1936 by Professor Egas Moniz, of Portugal. It has been used increasingly in all countries in the postwar years and has been carried out on about 12,000 people in the United Kingdom.

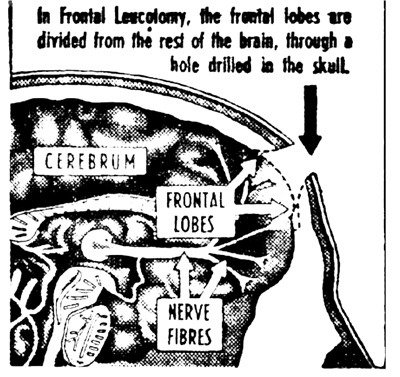

In simple terms, the operation consists of the cutting of the central core of white matter within the frontal lobes of the train, thus severing the association fibres between those lobes and other parts of the nervous system.

It is a “blind” operation. No one knows what part the frontal lobes play in the makeup of the brain. All that is known is that leucotomy sometimes relieves cases of grave mental illness. More frequently it does not and the patient often becomes worse. Or he or she may die of the operation, though that risk is not high, being about three in every hundred.

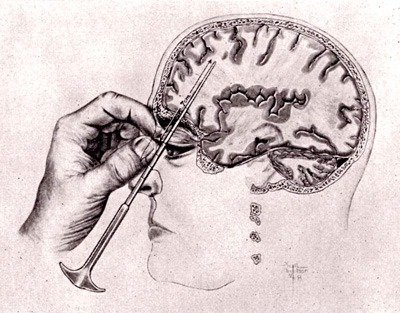

It is a “blind” operation for another reason. It is rarely ever carried out in the same way on two patients, because it is seldom that the cuts can be made in the same way. It is also a destructive operation – the work of the brain needle or of the leucotomy, a small instrument with a blunt rotating blade, cannot be reversed.

What the operation does in successful cases is to reduce tension. A patient with delusions, for instance, may not lose them, but they won’t upset him as much as formerly. A patient with feelings of persecution will still hold those beliefs, but they won’t disturb him.

When the operation does relieve, the patient is not cured, if you take “restored to normal” to be the proper definition of that word. He is less of a person and human being than he was before he became mentally ill. Dr. Maurice Partridge investigated leucotomised patients in England and found that 60 had been relieved of their severe mental illnesses sufficiently to return to civil life. ”

In view of the severity of the illnesses, this is sufficiently remarkable,” he reported. “Yet, every patient had deficits of some sort.

These deficits were listed in an editorial in the British Medical Journal last year:

The qualitative nature of this damage is well known. After operation patients may become more egoistic, tactless, dull, and lazy; they may be more irritable and quarrelsome; they may show lack of forethought and judgment.

More specifically, the “cured” patient has less ambition, less drive and, in some occupations – particularly those requiring any capacity for reasoning or concentration, they have less ability.

Of the 60 patients in Britain who returned to civil life, a solicitor was unable to hold down his job; two doctors succeeded, but rather shakily it was clear they were not what they had been before; a dentist never resumed practice. An engineer returned to his profession, but did not do very well; an advertising designer did very well after difficulties at the beginning; three trained nurses had to give up; the company director in a family firm had much difficulty; a tea taster was successful; secretaries found their jobs more difficult; clerks got by if kept to routine work.

The thinking of the relieved patients was on a much more primitive and concrete level. It is best illustrated by this dialogue, recorded in the Medical Journal, between the doctor and the patient:

Q: What does it mean when one says, “People who live in glasshouses shouldn’t throw stones?”

A: Well, of course, they shouldn’t, why, ha-ha, they’d break the glass.

Q: But is that what it means?

A: I suppose so; yes. of course,

Q: It’s not the answer you gave me when I asked you once before.

A: Oh? What was that?

Q: You said that it meant one should not criticise other people if one is open to criticism oneself.

A: Oh? (looks puzzled).

Q: Which do you think is the better answer?

A: The one I gave you today.

Harold Winch, age 63, of Harris Park, Sydney. For two years he suffered intense pain and in 1952 underwent a leucotomy operation at St. Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney. Today Mr Winch is an active man and helps out in his son’s electrical shop.

Harold Winch, age 63, of Harris Park, Sydney. For two years he suffered intense pain and in 1952 underwent a leucotomy operation at St. Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney. Today Mr Winch is an active man and helps out in his son’s electrical shop.

Summing up the changes in personality of a recovered patient, the doctor wrote, “There is a certain pedestrian quality of mind … a tendency not to occupy the leisure hours, to lack initiative in finding jobs to do or entertainments to enjoy. He may be considerate, but without the finer shades of consideration; he may even be sympathetic, but not readily or intensely so; he may be irritable, but his irritability will quickly subside.

He may be outspoken and direct, even a little tactless, but there will be no malice in that. His activities will be directed mainly toward pleasing himself, and he is unlikely to be altruistic or self-sacrificing . . . His prevailing mood will be one of cheerful equability . . .

Nevertheless, granting these losses in the finer qualities of mind, some of the recoveries have been remarkable.

The apparently incurable insane have been enabled to lead more or less normal lives. There is one instance, taken from a letter by a doctor to a medical journal. The doctor wrote:

“This patient was a schizophrenic (split mind) of 15 years duration; she was hand fed, faulty in bed, and exhibited frequent phases of violence; for more than 10 years she had been confined in a locked turbulent ward.

A leucotomy was performed three years ago and now she has taken her place in society, to the great delight of her mother.

No doubt her emotional faculties are not as deep as they would have been if recovery had been effected by other less drastic means, but until such is discovered we can justifiably resort to leucotomy in a case like this.”

Not all cases are as clear-cut or the decision as simple as this. With leucotomy the best results occur when the patient has been operated on in the early stages of his mental illness. The problem that can face a doctor is this. My patient has not responded to orthodox treatment and may get much worse. Should I resort to leucotomy now? Is something saved better than a total loss?

Transorbital leucotomy

An editorial on April 26 last year in the British Medical Journal, on “The Ethics of Leucotomy,” set out the general question that faces a doctor in these words:

“What is the damage to mental health which can be expected after leucotomy and how does it compare with the existing damage, which will otherwise continue? We must consider ‘the degree of happiness, of social efficiency, of power to appreciate and get the best from life, of kindness and affectionateness, of judgment and intellectual ability, which can be enjoyed by the patient or be restored to him if the operation be done or not be done. The decision can be a terrible one.”

What is gravely disturbing many members of the medical profession in Britain is the knowledge that leucotomy is no longer being confined to the apparently hopeless mental case.

Revelations that it is being performed on patients suffering from neurosis (“nervous, breakdown”), asthma and effort syndrome (“irritable heart”), and even high blood pressure and dermatitis, has provoked fiery protests in the correspondence columns of the British Medical Journal and The Lancet.

Br. D. W. Winnicott, an opponent of the leucotomy operation, said,

“The leucotomy enthusiasts have abandoned their initial claim that they cut the brain about only in the hopeless mental hospital case. The fundamental principle for which I think we must fight is that the human being has the first right to suffer, and even to commit suicide, with the brain, the somatic basis for the psyche, inviolate.”

Dr. David le Vay, another opponent of the operation, said,

“Leucotomy is essentially a method for achieving more efficient custodial care, and an even more efficient method of obtaining such care is by destruction of the whole patient-a method put into practice by some of our German colleagues during the war. It is monstrous to argue that such an operation on Mrs. X is worth while because of its beneficient effect on Mrs. X’s home-life. Does this justify the action of Mrs. X’s doctor in effecting the permanent spiritual mutilation of his patient?”

We can say the last word on the matter by adapting a remark of Mr. T. S. Eliot’s on the supposed therapeutic effects of time: ‘Leucotomy is no healer, the patient is no longer there.’

In defence of the operation for patients suffering from neurosis, other doctors wrote claiming that a neurosis, a nervous disorder without organic disease, was often as intractable as the more severe mental illnesses, the psychoses.

This was the stand taken by Dr. I. Aitkin:

“I maintain . . . that neurotics should receive intensive and prolonged psychotherapy (under which I include changes of environment and employment) before leucotomy is considered.But where all this has been done for several years, and the neurotic still remains a burden to himself, to his relatives and to society, and, of course, continues to be possessed by an unhealthy conscience, then frontal leucotomy should be justifiably considered for those types (eg, obsessionals) in whom experience has shown that the operation can be “successful in a large majority of eases.”

An even graver charge than that of “spiritual mutilation” is being made in medical circles. It is that leucotomy is being carried out in some mental homes in order to make things easier for the nursing staff.

A London psychiatrist, with a large practice, commented,

It is undoubtedly true. Mental homes are short of beds, with half the male nurses needed and without enough female nurses. For these circumstances, the staff are under pressure to use any treatment which might lessen the problem of nursing violent or infractory patients.

Against this disquieting background, the British Medico-Legal Society, consisting of doctors, lawyers .and judges, met recently, to discuss this controversial operation.

Members were dismayed by two allegations: that in some instances the operation has been carried out without, the patient’s consent, which is contrary to existing law in Britain, and that it has been performed on patients in recent months to facilitate divorce proceedings.

As the divorce law stands, a decree cannot be granted to the partner of a mentally ill person unless all known methods of treatment have been tried.

Another legal question that arises is whether the patient “cured” by leucotomy should be permitted to drive a motor car, in view of the fact that the operation tends to impair judgment, concentration and to make patients more reckless and Jess concerned with others.

So far, the British churches have taken no official stand on this grave matter. A few Protestant churchmen have claimed that the soul is damaged by leukotomy. Roman Catholics have made no protests.

Watching the situation with increasing unease is the British National Council for Civil Liberties. It is most disturbed by the new legislation passed in New South Wales, which permits the operation to be carried out in certain cases without the consent of the patient or of his parents or guardians. The general secretary of the society, Miss Elizabeth Allen, has protested strongly in these words:

The National Council for Civil Liberties has read with alarm the reports of recent legislation in New South Wales, which permits the performance of leucotomy operations on the mentally ill without consent of patients or relatives. Any suggestion that an operation of this kind, with its very uncertain results, should be performed without consent is an infringement of human rights. The growing tendency of a section of the medical bureaucracy to ignore the wishes of patients and their relatives is much to be regretted, more especially when the issue of public safety does not arise. In Britain, the right of a nearest relative to demand the release of even a certified mentally ill patient (provided he is not dangerous) has functioned as a safeguard in the patient’s interest.

The absence of this right in the case of those detained as mentally deficient is one of the main reasons why the standards of the mentally deficient services in Britain fall below those of the services for the mentally ill.

Any development, such as those in the New South Wales Act, which would further restrict the rights of patients and relatives in the field of mental health, will lead to a deterioration in the service and should be vigorously combatted by public opinion.

In the United Kingdom there is a growing feeling that this operation, which a doctor once described as being as scientific as banging a clock to make it go, should be more rigorously controlled than if is at present.

The kind of thing that many doctors feel must not happen in Britain is a lobotomy (removal of some of the frontal) performed recently on an American boy of 4 1/2, who was diagnosed as being a schizophrenic.

Here is an account of the case by two American doctors:

Our youngest patient was four years and six months at the time of operation. Absolutely incorrigible, destructive, assaulting, his face was a mass of bruises as the result of banging his face against furniture, in response to the most trivial frustration.

He had to be forcibly restrained in order to obtain a photograph. Unfortunately, the possibilities in this case will remain unknown because, after return home, and when things were going well, he contracted meningitis.

World’s News (Sydney, NSW : 1901 – 1955), Saturday 7 February 1953

Dr. Walter Freeman and Dr. James W. Watts study an X ray before a psychosurgical operation

- Rosemary Kennedy, sister of President John F. Kennedy, underwent a lobotomy in 1941 that left her incapacitated for the rest of her life

- In 2011, Daniel Nijensohna, an Argentine-born neurosurgeon at Yale, examined x-rays of Eva Peron and concluded that she underwent a lobotomy for the treatment of pain and anxiety in the last months of her life

- Warner Baxter who played the Cisco Kid underwent an ill advised leukotomy to ease arthritic pain

- Tennessee Williams criticized lobotomy in his play Suddenly, Last Summer (1958) because it was sometimes inflicted on homosexuals—to render them “morally sane”

- In Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ and its 1975 film adaptation, lobotomy is described as “frontal-lobe castration”, a form of punishment and control after which: “There’s nothin’ in the face. Just like one of those store dummies.” In one patient, “You can see by his eyes how they burned him out over there; his eyes are all smoked up and gray and deserted inside.”

- Over 60% of leucotomies were performed on women