Best We Forget?

1946

In Australia, during World War I, the Defence Act (1903) excluded people who were not substantially of European origin or descent from enlisting. When Aboriginal men and women who tried to enlist were rejected they were sent back to their communities and often arrested because they were not allowed to leave their prescribed area.

50 Aboriginal black trackers were left behind in South Africa at the end of the Boer war in 1902 because they were denied re-entry into Australia under the Immigration Protection Act, known as the White Australian Policy.

Instructions for the “guidance of enlisting officers at approved military recruiting depots” issued in 1916 state that “Aboriginals, half-casts, or men with Asiatic blood are not to be enlisted – This applies to all coloured men.” However, some Indigenous Australians who were of lighter skin colour with mixed European parentage enlisted by claiming foreign nationality. It was usually left up to the recruiting officer to decide whether to allow the person to enlist, so darker-skinned Aboriginals did sometimes slip through.

By October 1917, when recruits were harder to find and one conscription referendum had already been lost, restrictions were cautiously eased. A new military order stated: “Half-castes may be enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force provided that the examining Medical Officers are satisfied that one of the parents is of European origin.”

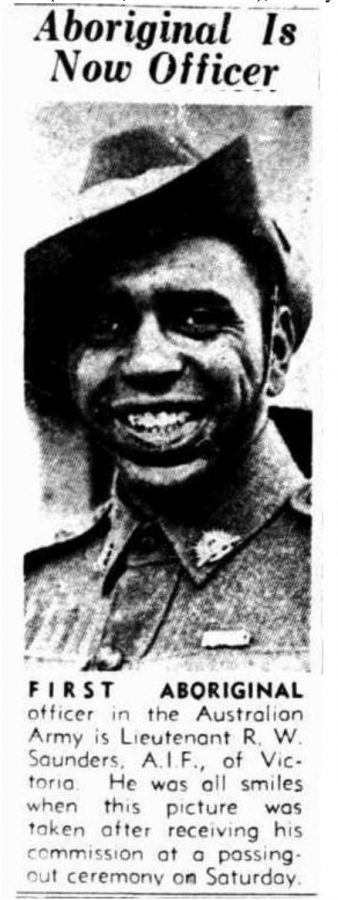

It was not until 1949 that all restrictions were lifted, enabling Indigenous Australians to join the Australian military forces.

Over 1000 Indigenous Australians fought in the First World War. They came from a section of society with few rights, low wages, and poor living conditions. Most Indigenous Australians could not vote and none were counted in the census. But once in the AIF, they were treated as equals. They were paid the same as other soldiers and generally accepted without prejudice.

Indigenous Australians served in ordinary AIF units with the same conditions of service as other members. Many experienced equal treatment for the first time in their lives in the army or other services. However, upon return to civilian life, many also found they were treated with the same prejudice and discrimination as before.

In 1940, the Defence Committee decided the enlistment of Indigenous Australians was “neither necessary, nor desirable”, but when Japan entered the war, the increased need for manpower forced the loosening of restrictions.

A group of about 50 Aboriginals were recruited in 1942 for scouting and reconnaissance in Arnhem Land and were known as the Northern Territory Coastal Reconnaissance Unit, RAE. This tradition is carried on today by Indigenous peoples who make up the bulk of the Regional Force Surveillance Units in NORFORCE, the Pilbara Regiment and the 51st Far North Queensland Regiment. Hundreds of Aborigines served in the 2nd AIF and the militia. Many were killed fighting and about a dozen died as prisoners of war.

In 1941, the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion was formed to defend the Torres Strait with other islander units created for water transport and coastal artillery. By 1944 almost every able-bodied Torres Strait Islander man had enlisted, though they never received the same rates of pay or conditions as white soldiers. By proportion to population, no community in Australia contributed more to the war than the Islanders of the Torres Strait.

http://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/history/anzac-day-coloured-digger-march#toc1